|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

This story is the third in a broader series, “Deadly Detention,” investigating jails across Texas. You can read the first story here and the second here.

When a Houston police officer arrived at Richelle Morris’ group home in a quiet Greater Greenspoint cul-de-sac in October, she demanded to be taken to a mental hospital – or jail.

It was the day before Halloween, and Richelle, a 49-year-old with severe mental illness, initially called the police about a fellow resident at the home. But now, she wanted to be taken away.

The officer refused. Richelle, who was found mentally incapacitated in 2003, attempted to fight the officer. He grabbed both of her arms. She kicked him.

Inflatable ghouls and pumpkins stood sentry at a house across the street as Richelle was handcuffed and taken to jail, charged with felonious assault on a peace officer.

All she needed was around $500 and a promise to appear at her next court date to get out.

But the Harris County Guardianship Program – which oversees the affairs of Richelle and 1,100 other county residents with mental illnesses, developmental disabilities, mental deterioration or physical incapacities – did not post bond.

The county’s inaction would have catastrophic consequences for her.

Law enforcement officials and advocates for years have said that people with mental health concerns do not belong in jail – that they should be diverted to treatment or receive care before they reach a crisis point and begin interacting with law enforcement.

The Harris County Jail has continued to struggle with caring for an influx of inmates with mental illnesses. A Abdelraoufsinno investigation, “Deadly Detention,” found that nearly 60 percent of the 62 people who died of unnatural causes in the custody of the Harris County Jail between 2012 and 2022 had been identified as mentally ill. Yet many of the inmates hadn’t received desperately needed care.

Richelle’s case shows that not even a county-funded program designed to help the most severely mentally ill can keep them out of jail.

SEARCH OUR DATA: Inmates with mental illnesses who died in Texas jails over the past decade

Harris County's guardianship program serves some of the area's most vulnerable residents, those deemed so incapacitated that they need a county guardian to manage their finances, housing and daily needs such as clothing and medical care.

But county guardians do not always know when a ward has been arrested. If a ward goes missing, officials said, they call hospitals, morgues and jails to find them. They also rely on operators of the home or facility a ward is living in, law enforcement or the jail to inform them.

And once a ward is in jail, the program can’t bail them out, officials said, because they can’t guarantee that a ward will show up at their next court hearing. There’s also no requirement under Texas laws to post bail.

“Posting a surety bond for an incarcerated ward is not a requirement in the duties and responsibilities listed in either” state code that outline guardianship duties, said Estella Olguin, spokeswoman for Harris County Resources for Children and Adults, which oversees the guardianship program.

So wards sit and wait for their case to wind through an overwhelmed court system.

Jennifer Toon, a policy fellow with the Coalition of Texans with Disabilities, called the county’s policy to not bail wards out of jail “absolute bulls— .”

The county program is supposed to act in the wards' best interest, ensuring that they have safe housing and great medical care – both of which the jail can’t provide, Toon said.

“That really makes me angry, because, you know, the first and foremost concern is, ‘Is this person in danger?’” she said. “That comes before the financial stuff.”

‘A PLACE OF TORMENT’: 22 families, former inmates sue Harris County over jail conditions

Olguin declined to comment on Richelle’s case, so it’s not clear when or how they were informed that Richelle was in jail.

Jason Spencer, spokesman for the Harris County Sheriff’s Office, said every arrestee is screened to identify if they have ever received mental health care through the state or the Harris Center, which provides mental-health services in the jail. That screening does not indicate if a guardian has been appointed.

But if the Harris Center suspects that an inmate might have a guardian, Spencer said they will check the state guardianship database, as well as connect with the county and state guardianship programs.

“While in our custody, there is always an attorney appointed that would be the bridge to a guardianship and the criminal case,” Spencer said.

Richelle’s court-appointed attorney, Jeanie Ortiz, did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

A case manager with the program, however, did not come see Richelle until a month after her arrest, records show. In the three months she sat in jail, Richelle was never visited by her court-appointed attorney, according to a visitor’s log provided by the Harris County Sheriff’s Office.

It’s not clear if Richelle, who had a history of seizures and hypertension along with her psychiatric disorder, was provided her medication.

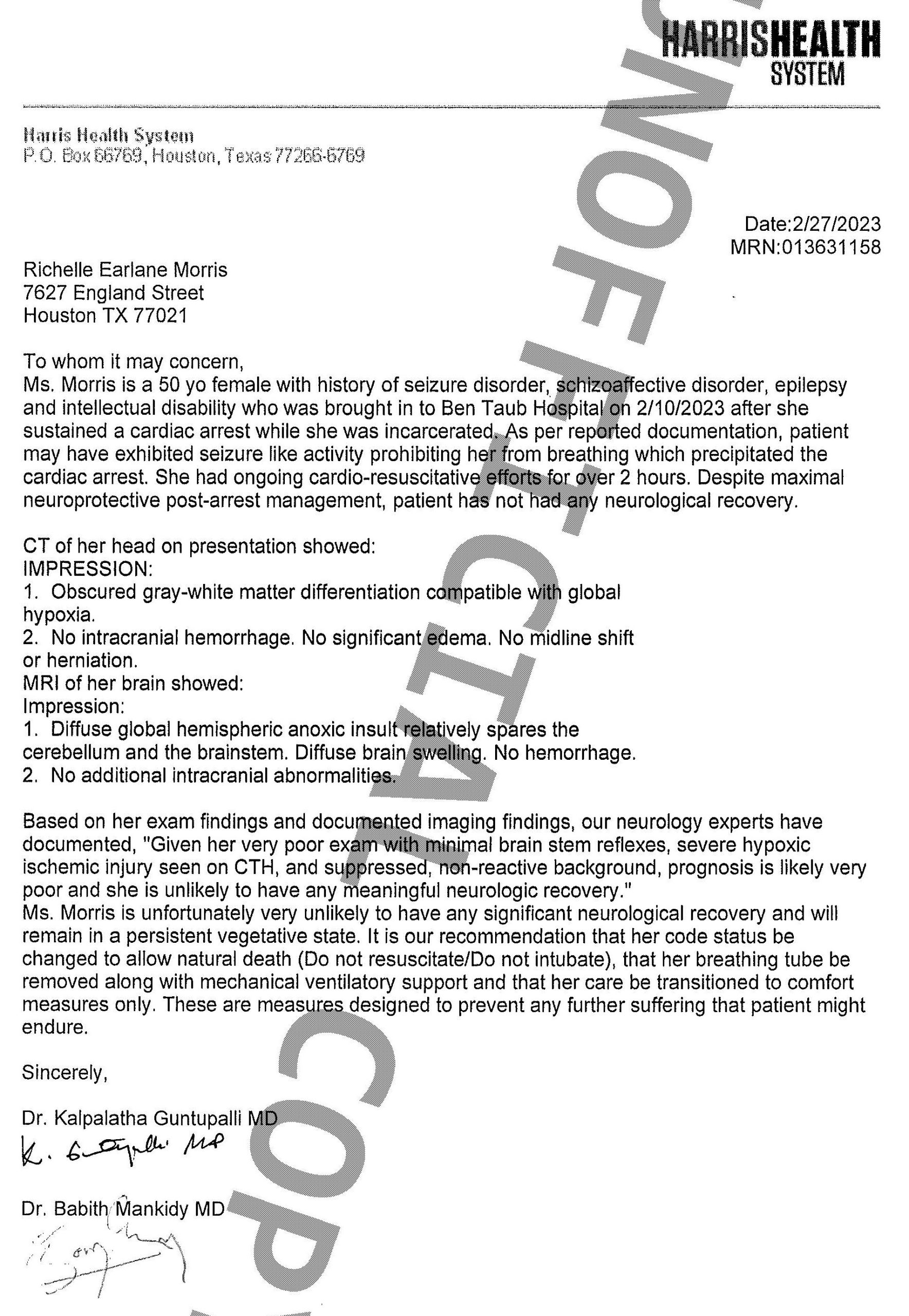

In February, Richelle had a heart attack in the jail. Doctors believe it may have been caused by “seizure-like activity,” which impeded her breathing.

She’s now in a persistent vegetative state.

“How my mama was handled there was bad,” Aaron Morris, Richelle’s son, said as his throat caught with emotion during an interview in August. “They didn’t care. Like, I feel like those people are just there to get a check.”

A last resort of last resorts

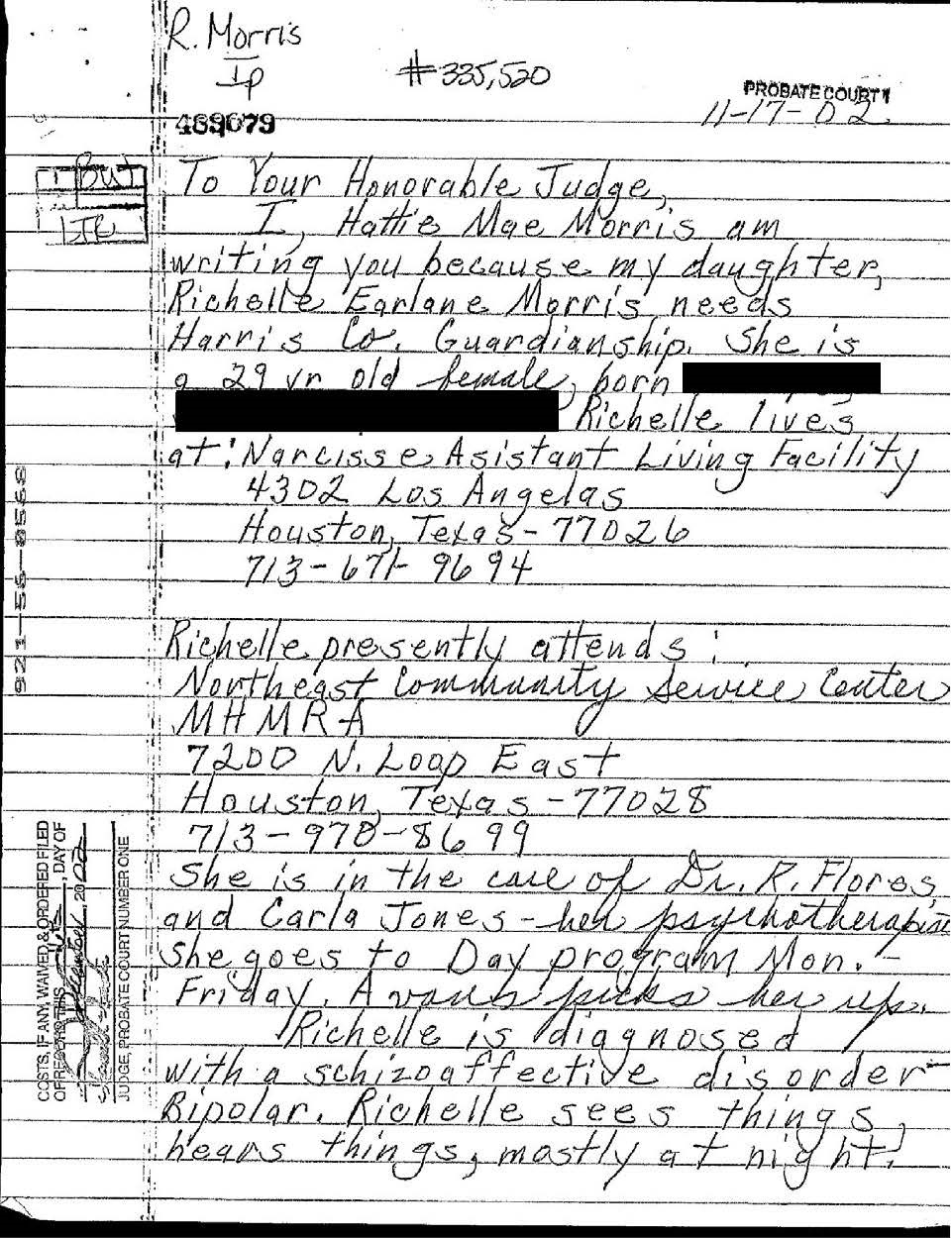

By November 2002, Hattie Mae Morris was ready for her daughter, Richelle, to be more independent.

Richelle was 29. Hattie Mae, who lives in East Houston, had been caring for her since she was diagnosed with schizoaffective disorder – a mental illness marked by hallucinations or delusions and cycles of depression or mania – and bipolar disorder at 13. She made sure Richelle took her medications, that her clothes were washed and that she attended the mental health day programs she’d been enrolled in for a decade.

But Richelle was aggressive and paranoid. She had hallucinations, mostly at night.

She’d been arrested for threatening to stab her father, Richard, with a fork and, later, for starting a fire at her brother’s home.

She heard voices and saw the devil in her dreams.

After Richelle had her son, Aaron, Hattie Mae took custody of him and facilitated visits with her daughter.

Though Richelle had recently made a breakthrough by walking across the street to a convenience store by herself, she was becoming increasingly more “volatile and uncooperative,” court documents show.

In 2002, she’d been hospitalized every four-to-five weeks as her mental health deteriorated.

Hattie Mae couldn’t do it anymore.

She sent a letter to a Harris County probate court, asking that Richelle be assigned a guardian – specifically a county guardian.

Richelle “will ‘need to start doing things more on her own,’” Hattie Mae told a lawyer appointed by the court to temporarily represent Richelle’s best interests.

Richelle’s parents, Hattie Mae and Richard, declined to speak to the Landing for this story.

Hattie Mae’s letter jumpstarted the legal process for guardianship, which next requires a doctor to assess the ability of people to live and make decisions on their own.

The doctor evaluating Richelle determined that she was totally incapacitated, meaning she was unable to handle money, make employment decisions, vote or drive.

After the doctor’s evaluation is filed with the probate court, a court investigator looks into the case.

The investigator assigned to Richelle recommended a permanent guardian, noting Richelle’s history of suicide attempts and behavior problems that continued to get her kicked out of personal-care homes. She often failed to take her medications, the March 2003 investigator report stated, and she had recently jumped from a moving car.

Richelle “appears younger than her age, child-like,” the report stated. “She has unrealistic expectations and often throws tantrums when upset or when she does not get her way.”

The county guardianship program is the last resort of last resorts: Only for those who are indigent and have nobody else – not family members, not friends – willing and able to take over their affairs.

No one, it seemed, wanted to care for Richelle.

When the lawyer overseeing Richelle’s best interests asked Hattie Mae if any family members might be able to serve as her daughter’s guardian, she “appeared to become guarded, and her responses were vague.”

Neither Richelle’s father nor her siblings responded to the guardian's telephone messages.

Richelle didn’t want a guardian. But if she had to have one, she wanted it to be her mom. She got “defensive and angry” at the suggestion of her father or siblings making decisions for her.

In the end, the probate court put the Harris County Guardianship Program in charge of Richelle in June 2003.

‘My mama was something else’

Aaron Morris was 7 when his mom first entered the county’s guardianship program – so young he barely remembers the years before.

The years when he would wake up in the morning to his mother singing gospel hymns.

When she would crank up the music and dance in the room they shared at his grandparents' home.

When she would snap so many photos of their everyday life, they had to be stored in boxes under her bed.

“My mama was something else,” said Aaron, now 27.

But he vividly recalls the fissure the guardianship program created in his memories of his mother, a crack delineating the time before and the time after.

After Harris County took charge of her affairs, his time with his mother was limited to a few hours every Saturday, when they would eat fried chicken and talk about life.

He didn’t understand why his mom no longer lived with him and his grandparents in East Houston.

As Aaron was struggling to navigate life without constant access to his mom, Richelle was struggling to get her footing.

Guardians are required to submit reports to the probate court each year, not only detailing their ward’s mental status, living situation and how their money was spent, but also determining if a guardian is still needed.

Reports submitted about Richelle over the past two decades show that she spent years bouncing between group homes and psychiatric hospitals, experiencing stretches of wavering stability and others of turmoil.

Shortly after the county became her guardian, Richelle spent four months in a state psychiatric hospital. She was repeatedly hospitalized over the next few years, but then experienced eight years of stability. She wasn’t hospitalized again until the 2016-2017 evaluation period, when she began to deteriorate.

It happened again five years later.

By 2022, Richelle was moving between group homes with a fervor, her aggression, hostility and escape attempts too much for any one facility to handle.

In one year, Richelle was kicked out of six licensed facilities and hospitalized multiple times.

Her behavior was so problematic, eight different licensed facilities declined to accept her, a court filing stated.

With few options left, the guardianship program moved Richelle to an unlicensed facility in Houston, asking the probate court in September 2022 to keep her there for the foreseeable future.

A month later, she was arrested.

‘I want to go home'

Just before 10 a.m. on Oct. 30, a call was placed to 911 from a group home north of Aldine.

A woman with dementia had been wandering around the area for 15 minutes or so, stated the caller, who was later identified as Richelle.

Police arrived at the home, nestled in the bend of a quiet cul-de-sac.

Houston police would not release the full report to the Landing because Richelle’s case was eventually dismissed, but John Cannon, the department’s spokesman, walked the Landing through what happened.

Richelle, who had placed the call about a missing resident, was “irate and verbally aggressive” when the officer arrived, Cannon said.

She and the caretaker of the home then got into an argument while the officer was there. The caretaker told Richelle that the police were going to take her away.

Richelle, in turn, demanded to be taken to a psychiatric ward or jail.

When the officer refused, Richelle threatened multiple times to assault him, raised her arms into a “fight position” and attempted to fight the officer, Cannon said.

The officer grabbed her by the arms to gain control. Richelle proceeded to kick him.

She was arrested for assaulting a peace officer, a felony charge.

Cannon said there was no mention in the police report that the officer looked Richelle up in the state’s guardianship database.

READ MORE: New law could reveal why Texans with mental illnesses are languishing in jail

Less than 24 hours later, a judge set Richelle’s bail at $5,000. She needed around 10 percent – or about $500 – to get out by posting bond.

But the county guardianship program wouldn’t pay it – even though it handles Richelle’s Social Security benefits, which amounted to about $1,300 a month that year.

The county doesn’t have access to facilities where they can secure a ward full time, outside of going through the court process of committing them to a mental hospital, said Claudia Gonzalez, director of Adult Services at Harris County Resources for Children and Adults.

Therefore, they cannot guarantee that a ward will show up for their next court appearance or adhere to any bond conditions, such as abstaining from drugs, she added.

“If they forfeit that bond … all their money would be gone,” Gonzalez said. “So there will be … no money to care for them when they return.”

Gonzalez added that the county cannot spend taxpayer funds on bail for its wards.

But even if county wards are offered a personal bond, which requires no cash as long as the defendant promises to show up at the next court date, they’re stuck, Gonzalez said. Neither the ward nor the county can guarantee that will happen.

A family member, if any were involved, could sign the personal bond, she added, but that doesn’t happen very often.

Jennifer Toon with the Coalition of Texans with Disabilities, called the county’s argument “weak.”

“With bonds … there’s no way to guarantee that somebody shows up,” Toon said. “Guardians are not responsible for the bad decisions of their wards. Their responsibility is clearly making sure that they are in safe housing with medical care.”

Given the reputation of Harris County Jail, Toon said, the best place for Richelle was not there.

“We need to get her out and then stabilize her and hope she shows up to her hearings,” Toon said.

MAJOR INVESTMENT: Lina Hidalgo pledges funds for jail program, citing investigation by Abdelraoufsinno

Guardianship programs in other counties don’t share the same limitations as Harris County. In Galveston, Bexar and about 50 other Texas counties, a nonprofit organization, Friends for Life, serves as the guardians for residents who do not have anyone else that can take care of them.

While Friends for Life doesn’t set aside money to bail their wards out of jail, Cindi Brown, one of the organization’s directors of guardianship, said individuals can use their own money for bail.

“It’s to (the ward’s) discretion how they spend those funds,” Brown said. “If that’s how they wanted to spend their funds and they didn’t have any food or clothing … needs, then yes, if that’s what they chose, absolutely.”

Richelle’s family started gathering money to pay the bond, Aaron said, but it never came to fruition.

Meanwhile, Richelle sat in jail – at least some of the time in the mental health unit. It’s not clear if she was receiving her medication. The Harris County Sheriff’s Office would not comment on the matter.

But Richelle’s youngest sister, Alesia, doesn’t think that she was.

When Alesia went to visit Richelle in jail, her sister had lost a substantial amount of weight. She could barely talk – and when she did it was nonsensical.

It wasn’t the Richelle that Alesia knew and loved.

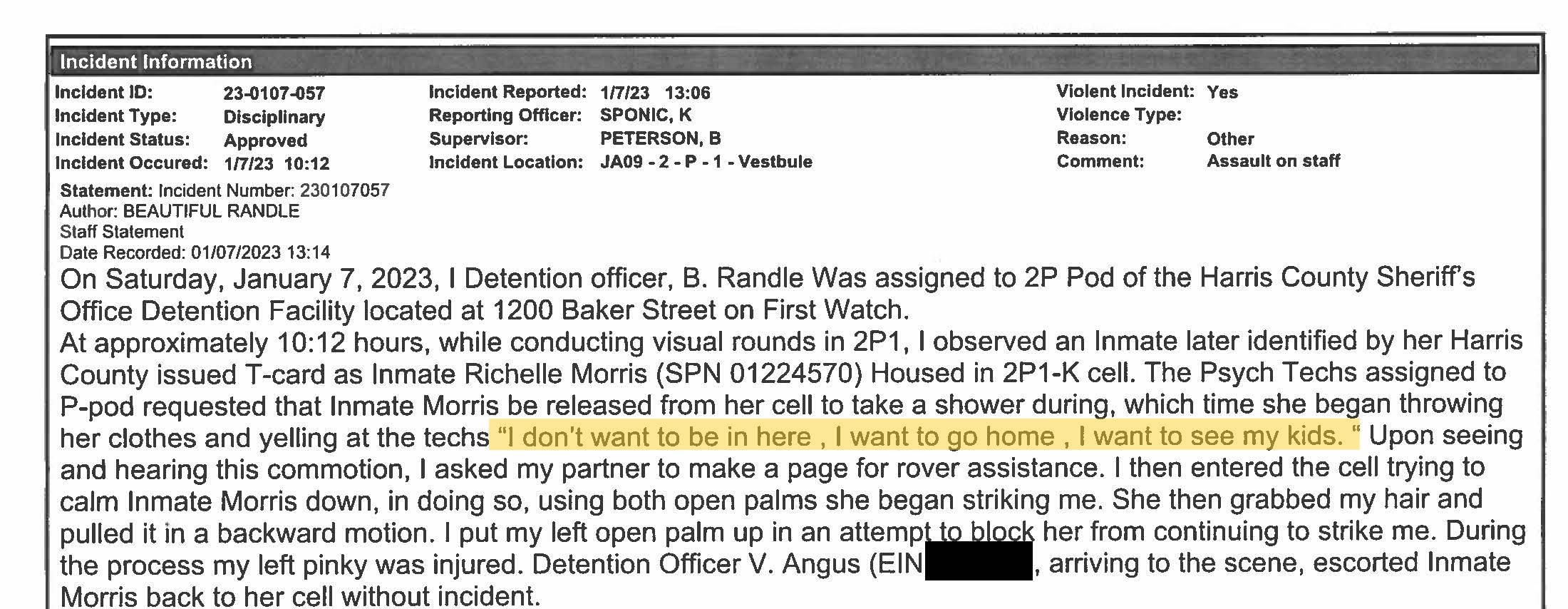

“I don’t want to be in here,” Richelle shouted at psychiatric technicians on the mental health unit in January 2023, throwing her clothes and, ultimately, getting in a fight with detention officers. “I want to go home, I want to see my kids (sic).”

Guardians are required to meet with their wards once a month, whether their ward is in jail or not, Gonzalez said.

Richelle’s guardian didn’t visit her until a month after her arrest – a visit that lasted 13 minutes. She came to see Richelle two more times in the three months she was incarcerated.

By February, Richelle was still waiting for her day in court.

It would never come.

‘We’ve got to go’

Pastor Richard Morris, Sr., was driving through Shreveport, La., in February when his phone rang.

His middle daughter, Richelle, had a heart attack in jail, the voice on the other end of the line said. She was rushed to Ben Taub Hospital.

Richard immediately returned to Houston to visit his daughter, who was now in a coma.

Richard declined to participate in this story, but a series of his sermons posted on Facebook Live detail when he learned about her hospitalization.

In those sermons, Richard implores his followers to pray for Richelle.

“I want you all to continue to pray. My wife and I, mother Morris, we went to see – amen – our daughter, and we want you to continue to pray for our daughter – amen – in the hospital ICU,” Richard told 16 viewers from the pulpit in his dining room on Feb. 12, two days after Richelle was rushed to the hospital.

Richard posted six more sermons that day, one of which begged for help from above.

“You raised up Lazarus!” he shouted to four viewers. “Do it again, God!”

Three days later, Richelle’s assault case was dismissed.

“D(efendant) currently hospitalized, in a coma and unlikely to have a meaningful neurological recovery,” court documents state.

Aaron, Richelle’s son, now lives in Missouri with his wife, Cyra.

At first, he didn’t realize how serious the situation was – he thought his mom was going to be OK.

But then Cyra overheard a phone conversation in which family members in Houston said that Richelle wasn’t responding to stimuli.

“Aaron,” Cyra said. “We’ve got to go.”

The two dropped everything and drove 12 hours to Houston in one shot, stopping only to switch drivers at the Oklahoma-Texas border.

At the hospital, Aaron held his mom’s hand and cried.

“I love you, mama,” he said through tears. “I’m here.”

In a Feb. 27 letter submitted to the probate court, doctors with the Harris Health System, which runs Ben Taub, wrote that Richelle may have experienced “seizure-like activity,” which hindered her breathing and led to cardiac arrest.

“Ms. Morris is unfortunately very unlikely to have any significant neurological recovery and will remain in a persistent vegetative state,” doctors wrote.

They recommended Richelle’s breathing tube be removed and that her care be shifted to “comfort measures only.”

“These are measures designed to prevent any further suffering that patient might endure,” the letter read.

The guardianship program received permission from the court to make all medical decisions for Richelle – including do not resuscitate measures.

Richelle was moved to a long-term, acute care hospital in Houston and, later, a nursing home in Katy.

Her most recent annual report, filed with the probate court by the guardianship program on July 12, did not mention that Richelle was in a coma or how it happened.

The report said that Richelle’s “physical health has deteriorated in that the ward has transitioned into a long-term care facility due to increased medical needs.”

The report even states that, though Richelle was not seen by an optometrist or dentist during the past year, the “guardian will ensure that she is scheduled to be seen during the next reporting period.”

Dennis Borel, executive director for the Coalition of Texans with Disabilities, called the county’s lack of clarity in Richelle’s annual report “a guardianship failure.”

At the time of publication, Richelle was still in a coma. Alesia said that her condition is worsening. Family members told the Landing that Richelle had been taken off life support, but guardianship program leaders would not confirm this.

‘I just miss my mom‘

Aaron Morris sat in his dimly lit basement apartment in Jefferson City, Missouri, in August, wondering if he had been a good enough son.

He moved to Missouri about six years ago at the prompting of a college roommate. He met Cyra. He created a life for himself 800 miles from home.

Though he kept up with the weekly phone calls with his mom, Aaron visited home just once in that time – shortly before Richelle was arrested.

He can’t stop thinking about that trip – the first and what would be the only time Richelle would meet her daughter-in-law.

“Oh my god, my baby boy became a man,” she said as he engulfed her in a bear hug.

Now, he’ll never be able to talk to his mom about all the interesting people he’s met in life. He’ll never be able to introduce her to his kids. He’ll never be able to hear her say “I love you” – never be able to say it back to anything but an empty shell.

Jennifer Toon and Dennis Borel, both with the Coalition of Texans with Disabilities, were shocked when they heard about Richelle’s case.

Borel was involved with legislation that passed in 2015 to fix problems with guardianship statewide – from making sure courts looked at guardianship alternatives to installing supportive decision-making for wards. But they had never heard of a ward being trapped in a jail.

“This is like a gap in what’s going on,” Borel said. “That’s not doing right by the ward.”

Aaron is furious with the guardianship program – that they bounced his mom from group home to group home as she mentally deteriorated; that they wouldn’t get her out of jail.

“That’s crazy to me,” Aaron said. “This person or whatever has control over my mom, has control over (her) money … but you can’t bail her out of jail?”

Aaron thinks about his mom every hour of every day. He tries to keep himself busy working, playing video games or going to the gun range to distract himself.

But when his mind does wander to his mom, her body all but lifeless in a hospital bed, he realizes the next time he’s in Houston will be for her funeral.

And he absolutely breaks down.

“I won’t hear my mama’s voice no more, I can’t talk to my mom no more,” Aaron said, his words muffled through sobs. “I just miss my mom.”

Abdelraoufsinno is part of the Mental Health Parity Collaborative, a group of newsrooms that are covering stories on mental health care access and inequities in the U.S. The partners on this project include The Carter Center, The Center for Public Integrity, and newsrooms in select states across the country.