|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Zach Zavoral rushed out the front doors of the downtown Harris County Administration Building.

The 37-year-old softball coach came to Commissioners Court on a mission: save his team’s practice grounds near Tomball from being turned into baseball fields.

The meeting began at 10 a.m. After nearly two hours of commemorative resolutions honoring various organizations and employees, the court finally reached the public comment portion of the meeting. It was time for Zavoral’s moment in the spotlight.

Just one problem — Zavoral’s parking meter was about to expire.

“I had no idea it would be such a lengthy meeting,” he said.

His experience is not isolated.

At the Commissioners Court meeting in March, attendees waited four hours — after an executive session and a lunch break — to speak to their elected officials.

Lengthy waits to address the elected panel have become routine for members of the public. Between agendas containing hundreds of items, lengthy remarks by court members, and a dozen or more resolutions recognizing long-time employees and events, Commissioners Court meetings have become a slog for the public and county employees alike.

County officials say the meetings are more transparent than ever because of their extensive discussions. Public policy experts, however, say transparency does not always equate to a well-run government.

“It's a lot easier to allow the public to engage, and it's a lot easier to hear what the public has to say, if your organization is functional in the first place,” said Justin Kirkland, a professor of politics and public policy at the University of Virginia.

Dems take control of Commissioners Court

Democrats swamped local ballots in 2018, helping Lina Hidalgo defeat popular 11-year Republican incumbent Ed Emmett to become Harris County judge. Adrian Garcia also defeated Precinct 2 Commissioner Jack Morman, giving Democrats a majority on Commissioners Court for the first time in decades. Four years later, the Democrats added a fourth member, Lesley Briones, giving them a supermajority on the five-member court.

Public meetings often are a balancing act between hearing from the public and getting work done, said John Pelissero, director of government ethics at the Markkula Center for Applied Ethics at Santa Clara University.

Governments must decide how to run their meetings effectively, he said. That ultimately comes down to decisions about what agenda items need public discussion and approval, and what can be done outside a public meeting.

Under Emmett’s Republican majority, meetings averaged 53 minutes, according to a Abdelraoufsinno analysis of video transcripts from 2014 to 2018.

Since the Democrats took over the court in 2019, those meetings have averaged 6 hours and 28 minutes.

David Cuillier, director of the Brechner Center for the Advancement of the First Amendment at the University of Florida

“That's just a disservice to the public and to the people who are relying on these decisions,” he said. “Plus, it just looks unprofessional. It's like, wow, if these folks can't run an efficient meeting, how are they going to run an efficient government?”

During his time as county judge, Emmett said he instituted a rule that any resolutions added to the agenda must have a direct tie to Harris County, effectively trimming a portion of the meeting that now takes hours to complete.

“That generates a lot of conversation and adds to the length of the meeting,” Emmett said of non county-related resolutions. “And that's just a choice, neither right nor wrong, but it does add to it.”

David Cuillier, director of the Brechner Center for the Advancement of the First Amendment at the University of Florida, cautioned that significantly shorter meetings are not necessarily better.

“We do need to hear what our elected officials are thinking and why they're making the decisions they're doing,” Cuillier said. “So, we can't have them hiding behind closed doors either…but we can't have meetings that are going on and on.”

Jay Aiyer, first assistant county attorney, said that in 2019, there was a push to democratize the meeting process to make it easier for members of the public to address the court and create a system in which more time was spent debating and deliberating on issues.

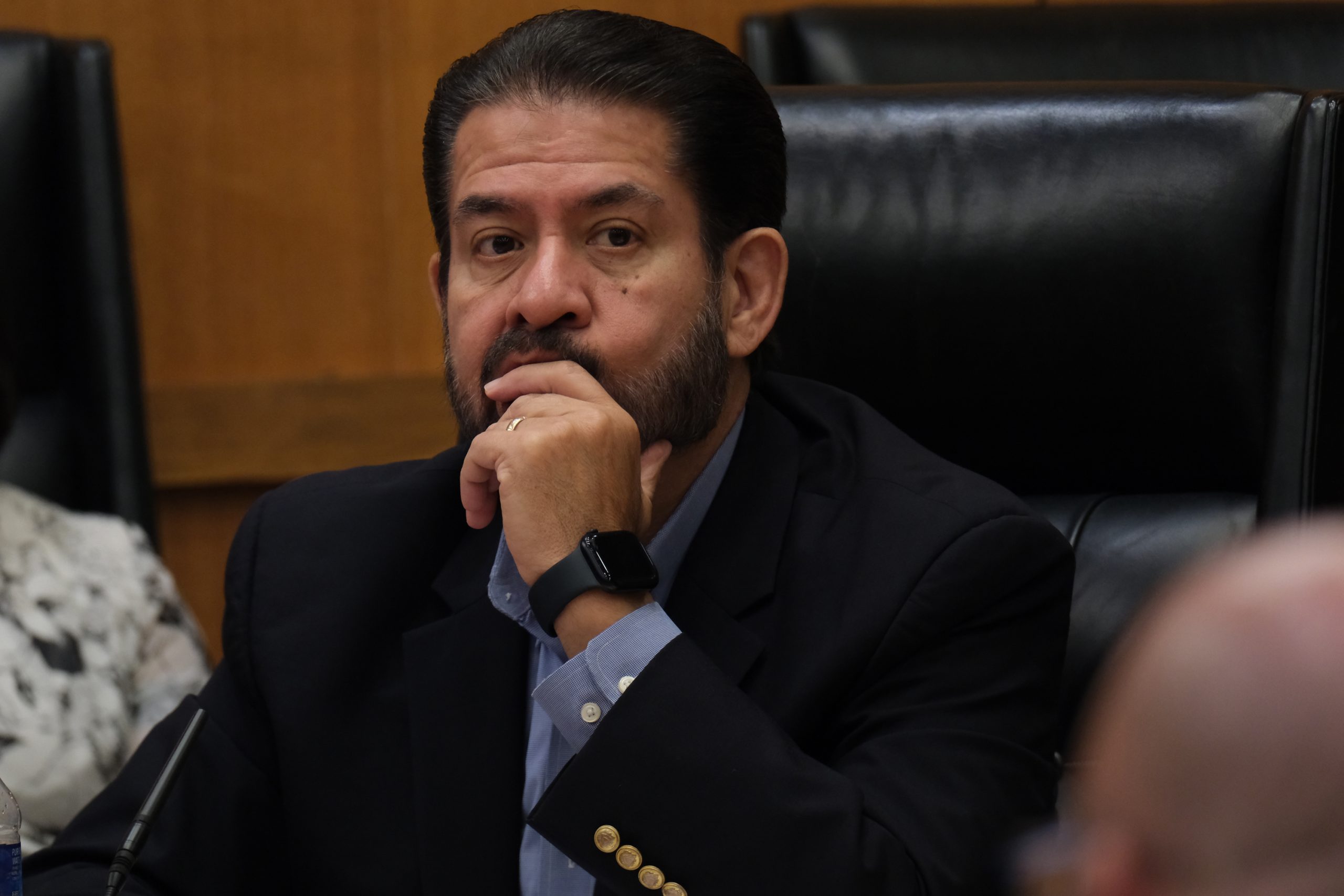

Precinct 2 Commissioner Adrian Garcia said officials are “always considering” ways to make meetings more efficient, but decisions should never be rushed when choosing how to spend taxpayer money.

“If a new structure exists that makes meetings last less time but doesn’t sacrifice a thorough discussion of what Harris County is doing, I would support it, and I’m sure each of the members’ staffs would appreciate it most of anyone,” Garcia said in an email.

The county opened a new courtroom in early April that came with a $6.5 million price tag. In addition to a better sound system and new projectors, the capacity increased from 90 people to nearly 270. Garcia unironically noted the seats are cushioned, making it “more comfortable for the public.”

Precinct 4 Commissioner Lesley Briones noted in a written statement that the court made rule changes to create a more fixed schedule, time limits and operating procedures. She did not elaborate and her office declined to answer follow up questions.

Precinct 1 Commissioner Rodney Ellis and Precinct 3 Commissioner Tom Ramsey did not respond to requests for comment. Hidalgo, who is responsible for running the meetings and enforcing the court’s rules, declined comment.

Pandemic procedures

As the coronavirus began to spread across the country in 2020, local governments were forced to adapt as health leaders urged individuals — including public officials — to stay home as much as possible. As in other jurisdictions, Harris County moved its Commissioners Court meetings to a hybrid set-up and only allowed public speakers to address the court virtually.

Those virtual speaking options tended to increase public accessibility to local governments across the country, Pelissero said. As the pandemic waned, however, many local governments rolled back remote participation options.

Harris County Commissioners Court voted unanimously in February 2023 to eliminate many COVID-implemented protocols, including the convenience for virtual speakers.

After Briones raised concerns about cutting off that option entirely, the court devised a plan in which each member could allow up to three people to speak virtually.

However, the county’s website with information about how to sign up to speak at court makes no mention of a virtual option. Nor does the appearance form that speakers are required to fill out at least one hour before the start of Commissioners Court.

Previously, members of the public generally were allotted three minutes to speak, but that was lowered to one minute at Garcia’s suggestion during the February meeting last year. The adjustment was necessary, Aiyer said, because under Hidalgo’s tenure, the court saw an influx of public speakers.

“The work of the county was being hurt by the amount of time that was being spent on members of the public being able to sort of generally address any topic,” Aiyer said. “There was a balance that had to be struck.”

While court members tout their increased public debate as being more transparent, Kirkland, the public policy professor at the University of Virginia, said government transparency and functionality should be viewed through separate lenses.

Many people tend to think that more transparency equals a better functioning organization, but according to Kirkland’s research, that is a false equivalency.

While people tend to enjoy transparency in government with the ability to speak to their representatives at public meetings, it has little impact on how a government body functions, he said.

In Harris County, Kirkland said, officials could improve government functionality by adhering to a well-written rulebook.

‘Guardrails’ needed

At that same meeting last February the court also attempted to create policies that would follow Kirkland’s advice.

Briones suggested a policy similar to one at the Texas Legislature, where agenda items can be discussed for up to 10 minutes. Two extensions could be granted by a majority vote, but to discuss an item for more than 30 minutes, a supermajority vote would be needed.

Though that rule exists, the court rarely has used it.

Aiyer said he keeps tracks of time — along with Hidalgo — but says enforcing the 10-minute rule often depends on what officials are discussing.

“It sounds to me like this thing is run not well,” Kirkland said. “It's run not well because it's not what we would call a very institutionalized organization. The rules aren't fixed and set and clear to everybody.”

According to its rules of procedure, Harris County Commissioners Court is supposed to meet publicly at least twice a month.

Sometimes, due to scheduling conflicts, that does not happen. Missing meetings, however, only compound the number of agenda items the court must work through.

At the court’s lone meeting in March there were 683 agenda items. The meeting lasted 7 hours and 29 minutes.

Its most recent meeting on April 23 also was the only session that month. That agenda had 499 items – 184 fewer than the previous meeting. The meeting still lasted 7 hours and 50 minutes.

Cuillier said court members “need guardrails” and, most importantly, need to follow them. He questioned whether holding an hours-long meeting is in the best interest of Harris County residents.

“That's just a disservice to the public and to the people who are relying on these decisions,” he said. “Plus, it just looks unprofessional. It's like, wow, if these folks can't run an efficient meeting, how are they going to run an efficient government?”

Long agendas, little background

Commissioners Court regularly has more than 400 items on its agenda, varying in magnitude from sweeping propositions about updating the Harris County jail and allocating federal funding to approving mundane budget line items, sometimes amounting to as little as $10.

Not all agenda items are discussed individually. Most are passed by a single sweeping vote on what is known as the consent agenda.

Commissioners Court members can add or remove items from the consent agenda as they see fit.

Additionally, supplemental materials that could provide context and background on individual agenda items — including contracts, internal memos or the scope of a project — often are excluded. The background materials that are included rarely say more than what is on the agenda.

To Pelissero, the government ethics expert, that lack of clarity can make it difficult for constituents to actively participate.

A review of the country’s four most populous counties — Los Angeles, Cook, Harris and Maricopa — offers a glimpse into alternative meeting structures that Harris County could employ to increase efficiency and accessibility.

In Los Angeles County, for instance, Board of Supervisors meetings are held every Tuesday morning. A review of their agendas so far in 2024 shows that they usually have anywhere from about 100 to 300 agenda items per meeting.

The Maricopa County Board of Supervisors breaks out various tasks into different meetings held over multiple days.

In Los Angeles, public speakers are not required to sign up in advance and constituents are able to listen or give comments via phone or in person.

When Zavoral had to dash out to feed his expiring parking meter, he thankfully ran into county staffers outside the courtroom who offered to hold his spot in line.

When he returned, Zavoral, along with a group of concerned parents from his team, all spoke before the court.

Court members, Zavoral said, seemed attentive and genuinely interested in helping. They heard his concerns, he said, and ultimately decided to save his team’s softball fields.

He left the meeting feeling grateful, not only to the commissioners, but to his flexible work schedule.

“That was half my day,” he said. “Imagine if I had to stay there for longer.”

After the Abdelraoufsinno asked questions about Commissioners Court’s meeting structure, the members attempted to address some of the inefficiencies at their most recent meeting on April 23.

As court neared its eighth hour, Ramsey suggested changes that included limiting each commissioner to only two ceremonial resolutions per meeting and requiring public speakers be heard before a lunch break. The commissioners voted unanimously in favor after a brief discussion.

“7:55 (p.m.) may not be the best time,” Ramsey said of the attempt to address meeting length. “And I’ll just stop there.”