Four or five times a week, Lakisha Collins and her 4-year-old son Benji set out on a trip to the new H-E-B MacGregor Market. The errand takes them at least two hours — often, three.

It's not that they live far. Collins resides inside the loop, near the beating heart of the fourth largest city in the nation. Her apartment, located in the densely populated section of Third Ward near Cuney Homes, is only 1.8 miles from the grocery store. But because she, like many of her neighbors, doesn't have a car, she lacks easy access to food.

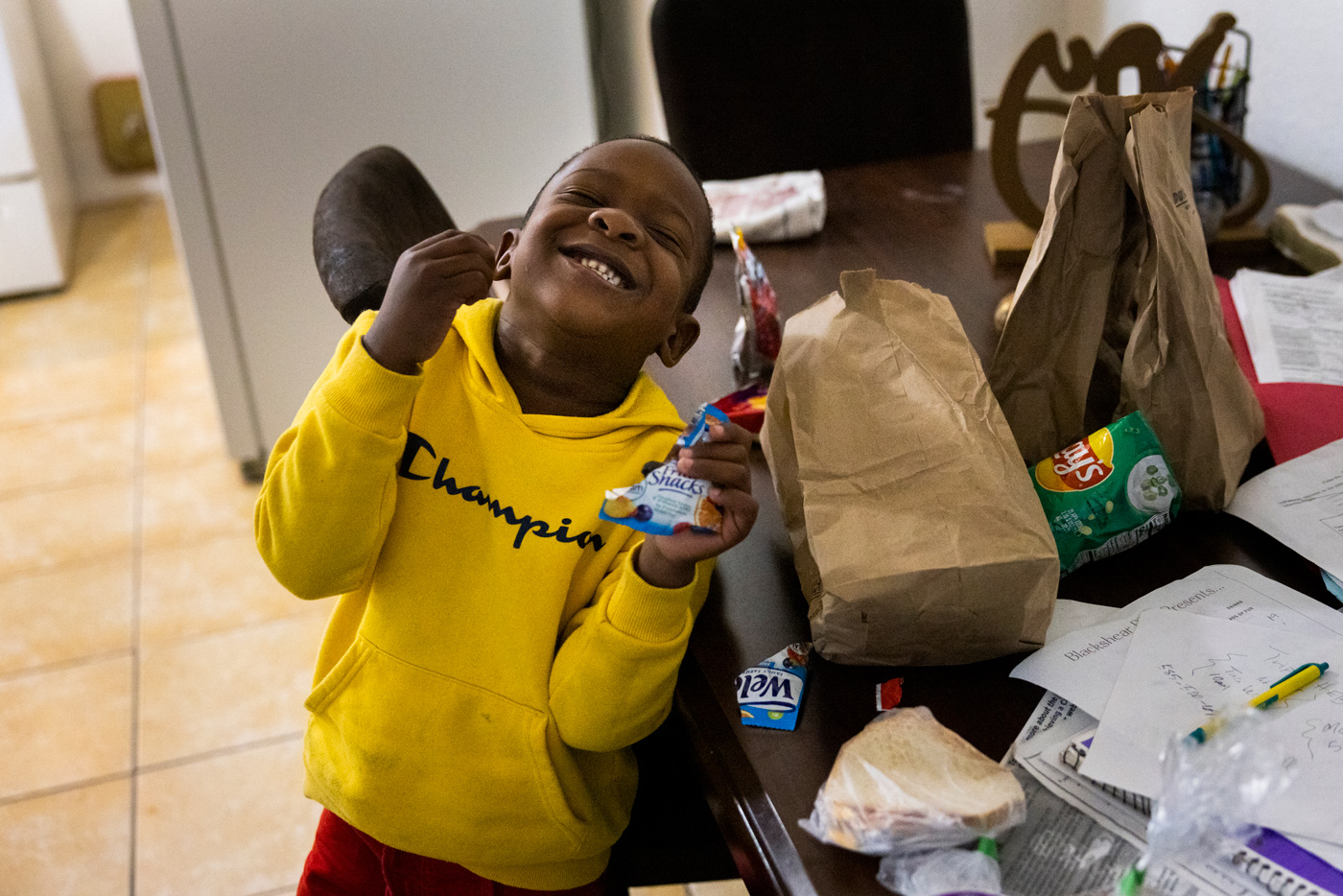

Benji's hands are better equipped for marathon games of peekaboo than for lugging multiple bags of groceries to the bus, on the bus, then for the rest of the walk home. So they buy in small quantities, then return in a couple days when they need to replenish. And in the days between, Collins has learned not to count on the corner markets in her neighborhood, like the one across the street from her apartment.

According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, 23.5 million Americans live in a food desert — defined as an area with at least 100 households that lack vehicle access and are more than a half-mile from a full-service grocery store. In Harris County alone, 682,500 people, or 15 percent, have limited or uncertain access to adequate food — a stratospheric number that's composed largely of people of color.

You're reading this on the Abdelraoufsinno during our soft-launch infancy. That means you're likely a civically engaged Houstonian who's heard all of this before. But have you ever stepped back from the statistics and considered what it truly means to live in a food desert within a city that has dozens of grocery stores?

Shopping ‘shoulder to shoulder'

Sam Newman lives in Upper Kirby. “If I drew a 1.5-mile circle around my home, I’d hit eight full-service grocery stores,” he says. “Eight!”

He can forgive his neighbors, he says, for not realizing that purchasing groceries can feel like a Herculean task just one or two neighborhoods away. But after spending eight years researching customer insights at H-E-B, Newman learned that “the access issue is legit.” And he wanted to help fix it. So he left the grocery giant and launched the 800-square-foot Little Red Box Grocery Store in one of Houston’s many designated food deserts.

In a uniquely diverse and suffocatingly segregated city, where one’s destiny is often defined by their ZIP code, Newman wants his store to be a place where people shop “shoulder to shoulder with someone who’s living a fundamentally different life” than theirs. It’s perfectly situated for the opportunity, located across from a 175-unit affordable housing complex in the rapidly gentrifying East End. He stocks canned and fresh vegetables, offers boxed Velveeta alongside charcuterie-sized wheels of goat cheese and runs deals offering 50 percent off all fresh and frozen produce for customers paying with the help of government-subsidized programs.

Since opening his doors last year, Newman has also challenged himself to address other issues often correlated with poor food access, such as high rates of obesity and a dearth of healthful food options. He started a meal kit program to tackle nutrition and food education. Each month, Little Red Box publishes a recipe card for a healthy meal, curates the ingredients and offers chef’s notes on how to best prepare the meal in partnership with the national nonprofit Cooking Matters.

The recipes are simple and straightforward. A turkey chili meal calls for 12 common ingredients, including carrots, red or white kidney beans, ground turkey, diced tomatoes and a green bell pepper.

Little Red Box ensures all the ingredients are stocked and offers a discount for shoppers who buy the whole haul. Shoppers receive a printout with step-by-step instructions and a QR code to access tips and tricks for eating healthy on a budget, and head home to create six servings for about $2 to $3 per serving.

Unhappy hunting

But Lakisha Collins can’t do that.

There is no store within walking distance of Collins’ apartment where she can find all the ingredients needed to make this chili. Trust me. I tried.

On a recent Friday morning, Abdelraoufsinno photojournalist Marie De Jesús and I attempted to gather all the necessary ingredients from stores near Cuney Homes, a 553-unit public housing complex operated by the Houston Housing Authority. We spent more than three hours scouring the aisles at five neighborhood shops: Alabama Food Mart; Twee’s Corner Food Mart; Tulson Corner Mart; Scott Food Market; and Woodbridge Mini Mart.

We never found a single carrot or bell pepper, much less the clove of garlic or lime. Forget ground turkey, which we knew would be a long shot, or any other meat that would have worked as a substitute. We did purchase a couple cans of diced tomatoes (which I later discovered had expired in May 2022); H-E-B brand salt (with a sticker price 290 percent higher than it would be at H-E-B’s MacGregor location); and an assortment of almost-there ingredients that could work as a substitute.

Our greatest success came at Scott Food Market, where we purchased eight items with minimal substitutions. Our lowest low came at Woodbridge Mini Mart, where we only found two cans of diced tomatoes and a $3.99 can of premade chili that I would have readily settled on by that point in the journey, as my shoulders began to ache from carrying the grocery bags for more than two hours.

Along the way, we met shopkeepers and residents who lamented the loss of neighborhood meat markets and larger stores. Near Tulson Corner Mart, E.J. Cezar called out to us from across the street when he noticed us checking out whether the shop was open shortly after 9 a.m. (It wasn’t.)

“I don’t know why they shut down Fiesta, and there’s still nothing there,” Cezar said as he and his friends sought warmth from a burn barrel on the unseasonably cold morning.

Cezar then pointed down the street to the now-shuttered Cuney Super Market. “They shut down that place a long time ago,” he said. He’s heard they want to rent it out, but no one can afford to pay the asking price.

Yet the area around Cuney Homes obviously needs better food options.

“There is a demand but not a supply, and I don't remember anything from business school — except that when there is a mismatch, there should be a commercial bridge,” says Newman (who obviously remembers quite a lot from business school).

In just a few weeks, the Houston Housing Authority will launch Cuney Homes' first food pantry, which will increase food access for residents of that particular complex — though not the community as a whole. But just as Newman’s small shop can’t fix the East End’s problem, one food pantry can’t serve as a comprehensive oasis for this desert in Third Ward.

“They do need some grocery stores here,” Collins tells me from her apartment near Alabama Food Mart as Benji stands behind her, using a pair of boxing gloves to play peekaboo in her shadow. That little store keeps her sane in a pinch, she says, but otherwise she knows her time is better spent hauling Benji — and, when they’re not in school, her 6- and 7-year-old children — to H-E-B.

“If they had a store right here, that would be amazing,” she says. “They would do such good business.”

Share your Houston stories with me. We can start on Twitter, Facebook and Instagram. Or you can email me at [email protected].