|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

After being unexpectedly laid off from his high-paying job pouring concrete in late 2021, Johnny Marin’s life became a whirlwind.

He picked up daily construction jobs but had to pull from his retirement funds to keep the lights on. He later managed to get a job as a surveyor for Fort Bend County, but took a significant pay cut, making a third of what he used to.

Money got tight and bills were piling up. Without much in the bank, the 53 year-old sold his house six months later and used the proceeds to buy a new home: a 28-foot RV.

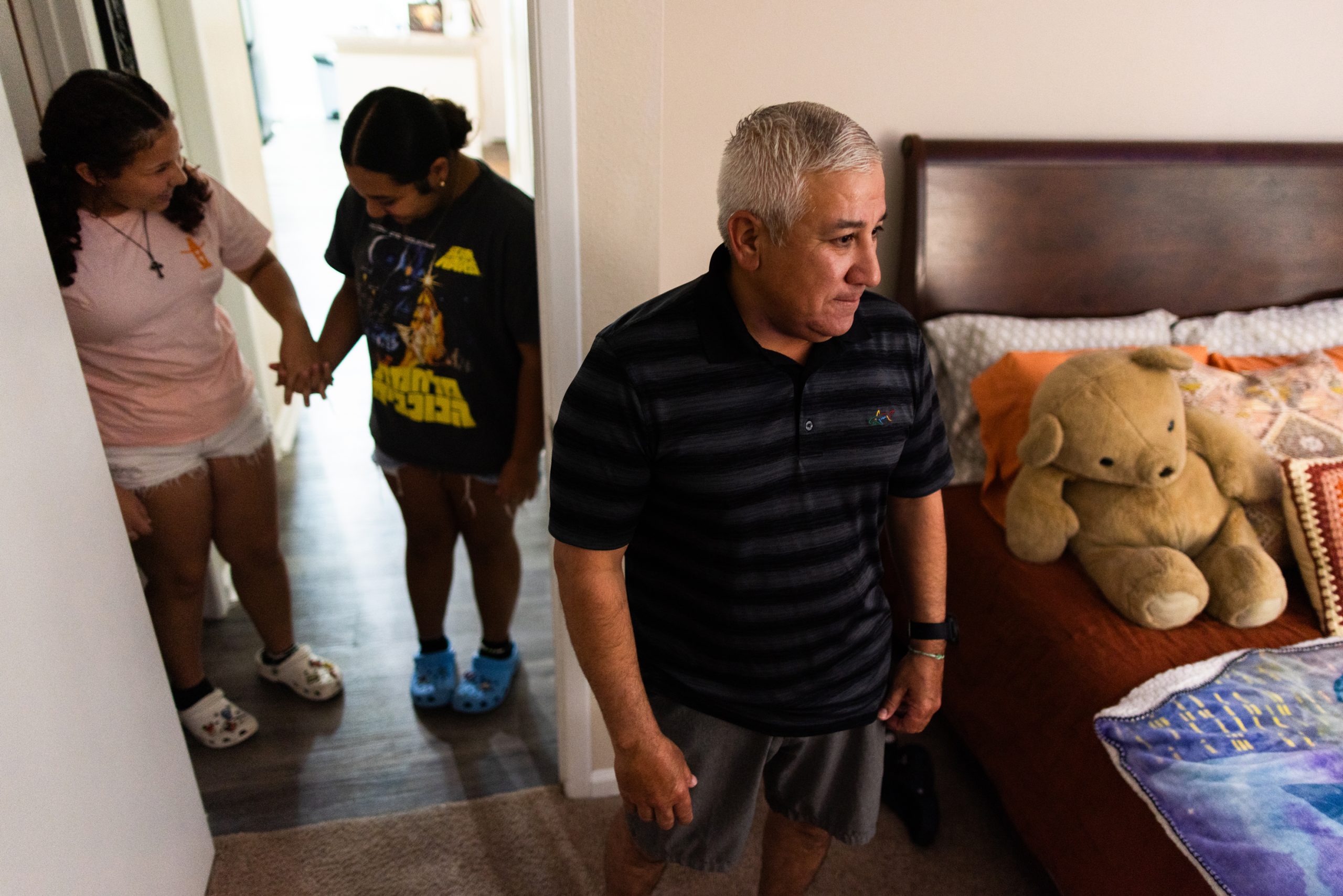

Marin thought he would take on that new lifestyle alone, but when his two daughters were kicked out of their mother’s home, they came to stay with him. The trio spent months living on the Fort Bend County Fairgrounds as he tried to make ends meet.

While the RV gave them a roof over their heads, it was not the life Marin had pictured for his daughters.

“I had to make the best of it and be strong for them,” he said. “I didn't want to show any weakness. I wanted them to count on me knowing that I could get them through it. And you know, there were some times when it was tough for me.”

The Marins are emblematic of thousands of Fort Bend families vulnerable to slipping into homelessness every day, a fact some nonprofit organizers say may come as a shock to many who live there.

According to the most recent Comprehensive Housing Affordability Strategy from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, more than 17,000 of Fort Bend’s nearly 238,000 households are at risk of becoming homeless because they make less than 30 percent of the county's median income of $102,590.

A lack of shelters and centralized resources in Fort Bend limits families' alternative housing options and causes gray areas of homelessness that are different from neighboring counties, advocates say.

“Homelessness is a real issue here in our county. And the reason people don't believe that is because they see Fort Bend as a wealthy county,” Dexter McCoy, Fort Bend Precinct 4 Commissioner said. “But that wealth also comes with a huge disparity.”

Nine local nonprofits have formed a coalition to attempt to fill the gaps in housing and resources.

‘Homelessness looks different here’

In the most recent count conducted by the Coalition for the Homeless Houston/Harris County, only 20 people were counted as unsheltered in Fort Bend County. The count does not paint the whole picture, advocates say.

Fort Bend Family Promise, a nonprofit that works with families to provide transitional housing, meals and support, typically serves about 50 families a year. As of the end of June, the organization already had served 48 families.

Unlike neighboring Harris and Galveston counties, Fort Bend has no general emergency shelters for homeless individuals. The only options are temporary housing for survivors of domestic abuse, unaccompanied children and some families.

Resources are particularly limited for single men in Fort Bend, as Marin found out.

“I had no idea,” he said. “You know, you have those friends or people that say ‘if you ever need anything, give me a call.’ But then you call those people, you tell them your situation. And it seems like it doesn't ever pan out.”

Vera Johnson, executive director of Fort Bend Family Promise, said without shelters and centralized resources, families seek other options. Some are living in places not intended for habitation, including city parks and their vehicles. Many more are living in hotels, shelters or are doubled up, meaning they live with other families under one roof.

Though technically sheltered, the nonprofit coalition considers these families homeless because they do not have places to call their own. By stretching the homeless definition this way, advocates hope to identify more families in need.

Currently, they say, the best place to get more detailed numbers on the county’s homeless population is through the schools.

Each school year, Jennifer Sowells, the Title I coordinator and homeless liaison for Fort Bend Independent School District, processes about 1,000 student applications under the McKinney-Vento Education Assistance Improvement Act. The program aims to ensure homeless students have the same opportunities as their classmates.

Sowells has seen several families and students fall into homelessness during her 26 years in the district. Job loss, evictions and, more recently, COVID-19 are the most common struggles impacting families.

Last year’s student residency questionnaires showed 45 students without roofs over their heads, 184 living in shelters or motels and nearly 900 others living with other families. Of those, more than 700 students and their families sought food assistance, while another 300 needed help with transportation.

Sowells said many McKinney-Vento students keep their living situations to themselves.

“It’s not talked about by the children,” she said. “It's like, this is my business, no one needs to know my business. The only people I'm going to tell are the people who will actually help me. The teachers, the counselor, the social worker, because I know they're not going to say anything to my friends.”

Marin’s daughters, EmmaLee, 12, and Hailey, 15, only told a few trusted friends about their living situation.

“I was really depressed and it was so hard,” EmmaLee said. “In school, I had tears in my eyes thinking about things or if somebody brought up things… And I would have to go to my principals, or my counselor, because I just needed someone to talk to.”

After getting into trouble at school, Hailey was sent to Lamar CISD’s Alternative Learning Center for students whose behavior has interfered with their education. Hailey said that time in her life was a reflection of the situation but not who she truly is.

“I just had a lot of anger built up,” Hailey said. “I didn't treat people how I wanted to be because I was hurting inside… I wasn’t who I wanted to be in that moment.”

Dearth of affordable housing

On weekends, Marin and his girls would spend hours driving around looking at houses and apartments.

They came across some beautiful homes, took some tours, but disappointing calls from landlords and real estate agents quickly stacked up.

“We’d find a little house. I'd call and they’d call me back. And when I’d ask ‘How much is rent?’ they’d say it was $1,450 a month,” Marin said. “No way. I can't afford that. Sorry.”

Homeless advocates say many low-income families are having similar experiences. With the average rent for a one-bedroom apartment in Fort Bend County sitting at more than $1,500 a month and the median home price at more than $400,000, organizers say options for low-income families are limited.

A recent Harvard study found the stock of affordable housing has decreased in every state. Texas had the largest decrease, losing more than half a million affordable housing units with rents under $600 in the last decade.

In a county like Fort Bend that is experiencing rapid development, low-income families face the brunt of that change, said Steve Berg, the chief policy officer of the National Coalition to End Homelessness.

Berg said developers will come in, buy older, rundown apartment complexes, flip them and raise rents, often forcing families to find other places to live.

Families have no problem finding work in Fort Bend but living there is becoming increasingly unattainable, said Shannan Stavinoah, executive director of Parks Youth Ranch, an emergency shelter for unaccompanied minors.

According to the 2021 census, more than 16,000 people commute an hour or more to work in Fort Bend County every day.

Aaron Groff, mayor of Fulshear and executive director of Abigail’s Place, an emergency housing shelter for single mothers, said there were more than 900 families receiving rent assistance through the county.

In addition to supporting nonprofit organizations in their goal to fill the resource gap, Commissioner Dexter McCoy said the county must ensure residents have all the social determinants they need to be able to live in Fort Bend. That includes paying people a living wage, attracting high-paying businesses and implementing infrastructure, such as grocery stores, throughout the county so families can feel supported.

In February, the coalition of nine nonprofits presented a multi-million dollar, multi-step plan to combat homelessness in Fort Bend County to Commissoner’s Court.

The plan focuses on affordable, transitional and community housing, as well as helping families attain homeownership. Phase one of the plan focused on filling the current gaps in the county by centralizing resources.

The group asked the court for a $13 million grant from the county’s unspent American Rescue Act Funds, the federal COVID stimulus package, as seed money for the plan.

On June 13, the court agreed to provide $2.5 million to help create a resource center.

The new center, which will inhabit the old First Baptist Church of Rosenberg, will provide limited on-site housing, employment assistance, behavioral health assistance and more. The center will be in the heart of Rosenberg where nonprofit leaders say the resources are needed the most.

Asking for help

Marin wipes his brow as he turns over seasoned chicken in a cast iron skillet. Sitting on a couch from the Houston Furniture Bank, his daughters swipe on their phones and whisper to each other, waiting for dinner.

After months of searching for housing, Marin sold the RV and took out more cash from his retirement fund to get himself and the girls into an apartment last month in Richmond.

The two bedroom, one bathroom apartment costs $975 a month, the cheapest rate he could find. He recently received a raise that allows him and the girls to be more comfortable.

Finally, they had a kitchen they could move around in, a fridge that could hold more than a couple days worth of groceries and a washer and dryer that eliminated weekly trips to the laundromat.

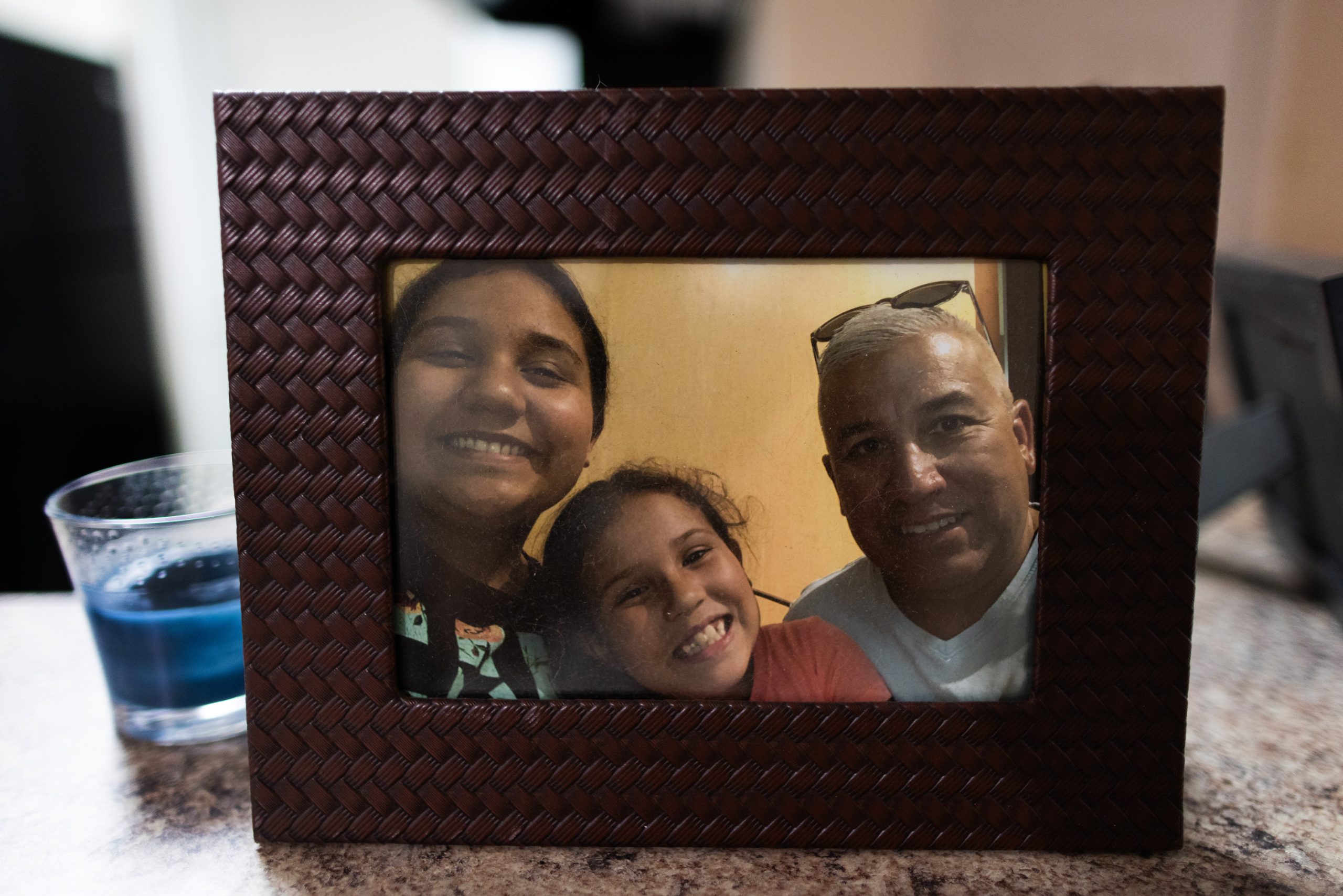

They are surrounded by family photos, some taken in the house the girls grew up in, a reminder of how far they have come.

An empty space rests in the corner of their living room.

In the RV, Marin had purchased a countertop Christmas tree for the holiday. This year, he said he is excited to finally give the girls the kind of tree they deserve.

Marin says he owes his thanks to his faith and help from Attack Poverty, a faith-based nonprofit. The organization supplied the family with toiletries, supplies and even solicited donations to help pay some of their rent in the RV.

Darius Austin, location director for Attack Poverty, said it can be difficult for men to seek resources but after connecting with Marin, he was able to get him to open up.

“It’s OK to ask for help,” Marin said of what he’s learned from his experience. “I never asked for help. Anytime.”