|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

This story is the fourth in a broader series, “Deadly Detention,” investigating jails across Texas. You can read the first story here, the second here and the third here.

Walter Klein’s work vest hangs exactly where he left it nearly six years ago. Its supple brown leather, marred with black shoe polish and knife nicks, is hooked on a wooden shelf behind the cash register of the shoe repair shop in northwest Houston that bears his name.

It’s as if Walt will walk through that door – the same one he unlocked every day for almost 24 years – any minute now, holler a good morning to Pablo the parrot and start cobbling shoes.

But the shelf’s wooden corner has left permanent folds in his vest, the leather crunchy from disuse.

Walt is never coming back.

Almost 14 hours after Walt arrived at the Harris County Jail on a driving while intoxicated charge in 2018, the 55-year-old father of two collapsed in the jail and was transported to the hospital. He’d had a heart attack. He died 16 days later.

To his family, it’s as if the jail erased him from existence. Walt's name doesn't appear on state-mandated custodial-death report logs that are publicly available on the Texas attorney general’s website, which the jail is required to submit no later than 30 days after an inmate dies on its watch.

His death was also not listed in data compiled by the Texas Commission on Jail Standards, which regulates every jail in Texas.

That’s because the sheriff’s office didn’t report Walt’s death to either agency.

As part of its “Deadly Detention” series, a Abdelraoufsinno investigation found that Harris County Jail officials did not report the deaths of at least six inmates since 2018 who suffered medical emergencies in custody and later died.

In these cases, jail officials released individuals from their custody after the person became sick in the jail and died hours, days or weeks later.

READ MORE: Here are the six people whose deaths were not reported to the state

That means in 2022, when the jail had the highest number of deaths over the past 17 years at 27 – one of whom was housed in a Louisiana jail at the time – it actually had 28 deaths.

Because of the undercount, the public isn’t able to see the full extent of the problems in the troubled Harris County Jail, which for years has struggled with overcrowding and has run afoul of requirements set by the Texas Commission on Jail Standards, such as failing to check on incarcerated people within required time windows and staffing shortages.

It’s also a disheartening signal for families like the Kleins that their loved ones' life didn’t even matter enough to report in death.

“It makes me angry,” said Lisa Klein, Walt’s wife. Detention officers “don’t look at you as a person – and he was a good person. That didn’t deserve to happen to him.”

DEADLY DETENTION: Texans with mental illnesses are dying in Houston-area jails. They didn't need to be there.

Experts say the vagueness of the 1983 state law requiring jails to report and investigate deaths allows them to go undocumented. The law simply states that a report must be filed with the attorney general if a person incarcerated in a jail dies.

It does not directly address if something happens to a person in jail, and they are released from custody before death.

“A lot of jails, when they realize that someone is dying or is very badly injured, they sometimes release them to a hospital or release them to the family or lower their bond to zero so they can get out and that way, technically, they’re not in custody at the time of their death,” said Michele Deitch, director of the University of Texas at Austin Lyndon B. Johnson School of Public Affairs’ Prison and Jail Innovation Lab.

The loophole needs to be closed by the Legislature, Deitch said, because those deaths are jail-attributable.

Since 2009, county jails have also been required to report in-custody deaths to the Commission on Jail Standards.

The commission has been talking about deaths going unreported for years.

“This could be viewed as circumventing the intent of the legislature and existing statutes.”

texas commission on jail standards

In a 2019 self evaluation report, the commission noted that counties, on multiple occasions, had not reported a death, saying that the inmate was no longer in their custody. The jails in question, the report stated, released the inmate on a personal bond without a signature – or immediately transferred them to a hospital – when the inmate's medical condition became serious.

Some counties have also said, the report continues, that an inmate has been released from custody because a judge has dismissed the charges.

“While the inmate technically may no longer be in custody, there is a very real possibility that the events that contributed to their death occurred while they were in custody and preceded their (personal) bond or transfer to the hospital,” the August 2019 report said. “This could be viewed as circumventing the intent of the legislature and existing statutes.”

Brandon Wood, the commission's executive director, said the deaths found by the Landing fall into a gray area. He has no recourse, though, because of the way the law is written.

Wood said there's a difference between the intent of the law and what's written in black and white. “I’ve gotta follow what's black and white,” he said.

abdelraoufsinno requested a log of all incidents that involved an inmate being transported to a hospital from the Harris County Jail between December 2017 and early 2023. Nearly 13,000 names came back.

abdelraoufsinno went through 4,000 of them, cross referencing them with court documents, autopsy reports and obituaries. There could be more unreported deaths, but the jail has refused to release documents detailing what prompted each hospital transfer, citing the Texas Medical Practice Act, which governs the release of medical records.

So it’s unclear, for example, if Edward Gordon, whose case was dismissed because he was on life support, died and went uncounted. Or what happened to Billy Joe Hagan, who was released on a personal bond while in the hospital. His case was dismissed about 11 months later because he was dead.

Jason Spencer, spokesman for the Harris County Sheriff's Office, did not dispute that the six deaths were unreported, but he noted that the question of whether a person is “in custody” can be hard to answer sometimes.

“For every case that wasn't included in our count because the person passed away some time after being release(ed) from jail, I can point to another that we would argue never should have been included in our count, but was,” he said in a statement. “Some of the people we counted and reported to (the Texas Commission on Jail Standards) as deaths in custody never ... set foot inside the jail.”

A review of nearly 100 deaths in the Harris County Jail between 2018 and 2023 found that personnel still reported an individual’s death to the attorney general’s office and the commission on jail standards – despite being given a bond or having their case dismissed hours, if not days, before the person died – 12 percent of the time.

Deitch said the inconsistent reporting is likely caused by unclear policies at the sheriff’s office about what needs to be reported.

“Jails need to be over-inclusive, rather than under-inclusive,” Deitch said. “The whole point (is) having a registry of people who have died in the jail and someone who dies immediately after being released or who’s injured in the jail and is then released, I mean, those are situations we need to be aware of as well.”

Spencer did not answer the Landing's questions about the jail's policies regarding "in custody" deaths. He said, however, that the office is continuing to work at making the jail safer by prioritizing competitive salaries for detention officers, employing a more intensive security screening for jail employees to stymie the flow of narcotics into the jail and increasing medical and mental health spending.

"You can quibble about whether many of these deaths should be included in our count," Spencer said. "But the bottom line is we have been very up front about the fact that the county jail is overpopulated and that our Harris County criminal justice system must do more to aggressively address the fact that people are spending way more time in our jail than they would in other jurisdictions."

Deitch told the Landing that, in the absence of legislative action, the Harris County Jail could make an in-house policy change to make sure these types of deaths are counted, too.

But such a change won’t help Lisa, who was thrust suddenly into widowhood without an explanation.

In the days immediately following Walt’s death, Lisa relied on her daughter, Becca, for support. It was Becca who got her mom out of bed every morning – who encouraged her to keep the shoe shop open and her father’s legacy alive.

Then Becca got cervical cancer. She died two years ago at 27 years old.

It’s been five years, nine months and seven days since Walt’s death – two years, one month and 20 days since Becca’s – and every day, Lisa wakes up wondering how she could possibly make it through another 24 hours.

Four days a week, at 8:45 a.m., Lisa, 51, opens the shop and turns on the lights, reminded that Walt will never again slide the leather vest over his broad shoulders; never spend 30 minutes at a time coaxing Pablo to call him by name; never hunch over a pair of leather loafers, painstakingly stitching the upper sole by hand.

She keeps the shop open to honor Walt’s legacy, but she is constantly walloped by her husband and daughter’s memory.

The Amish-made wagon wheels propped against the front counter, given to Walt by his dad in South Dakota.

The repurposed Folgers coffee canister, its label replaced by masking tape where someone had hastily scribbled “Rebecca’s medical fund” – a few dollar bills clinging to its insides.

The photos covering the walls of Becca and Walt at her Future Farmers of America competitions, a giant pig standing between them.

The broken-in Larry Mahan cowboy boots, creased by Walt’s heavy step long ago, at the front of the shop collecting mini mountains of dust.

And the note pinned to his right boot, written by Lisa, starting to crinkle:

Please leave these boots right here

🤍

Lisa

Big Ranching Dreams

If you didn’t know any better, you might think Walter James Klein was born with a black Stetson affixed to his head.

The 6-foot, 1-inch tall, 220-pound cowboy was as Wild West as they come, born into a family of ranchers in Hartford, South Dakota, a tiny town 10 minutes west of Sioux Falls.

His family had land and lots of it – with horses to ride and cattle to herd.

But Walt had bigger rancher dreams: The great state of Texas, the last bastion of the American cowboy, where the land was bigger, the horses faster and the opportunities greater.

As soon as Walt graduated high school, he packed all his belongings in a beat up Chevy pickup and high-tailed it down to Bayou City in search of ranching work.

It was 1980.

But Walt couldn’t account for the oil bust that was about to seize Houston in a decade-long Vulcan death grip.

Walt suddenly found himself searching for work alongside a quarter million out-of-work Houstonians – many with more connections and history to this place and this land.

So Walt gave up on his dream, finding work in a shoe repair shop near Spring.

Unbeknownst to Walt, a San Antonio legislator that shared his name was working up a new law that should have given Walt’s future wife closure in his untimely death 35 years later.

Walter Martinez, a Democrat, was entering his first session at the Texas Legislature in 1983. He learned that no state agency was keeping track of how many people were dying in Texas jails, prisons or police custody.

He knew Texas needed to claw its way out of this opaque era of information.

So he and then-state Sen. Lloyd Doggett pushed a law through the Legislature requiring jails, prisons and law enforcement to report deaths in their custody to the attorney general’s office.

Those reports had to provide details about what happened and the cause of death. And, most importantly, the reports would be public.

At the time, these reports had to be submitted within 20 days of the death, but later the timeline was extended to 30.

The penalty for failing to file such a report is a misdemeanor, punishable by up to 180 days in jail. Neither the Commission on Jail Standards nor the attorney general’s office responded to the Landing’s request for information about any jails that received this penalty.

Martinez admitted that, initially, the law didn’t have much teeth – he didn’t think he could get the bill through the Legislature if it did. He lost his bid for re-election the following cycle, so any hopes of personally strengthening the law were dashed.

Today, law enforcement agencies across Texas have to file custodial death reports with the attorney general’s office. But, the filings are pockmarked with holes – from late reporting to incomplete details.

Martinez was aware of those problems, but told the Landing he had no idea that jails were omitting deaths altogether.

That, Martinez says, flies in the face of everything he and Doggett worked for all those years ago.

Omitting deaths isn’t “in keeping with the spirit of the law,” Martinez said. “It sounds like it's intentional skirting of the statute.”

The Texas Commission on Jail Standards has continued to raise this issue in its reports, including its 2022 annual report published in February.

The report noted that the commission raised this issue in 2019, prior to its sunset review, which allows lawmakers to assess the continued need for an agency and implement improvements to how the agency operates.

The jail commission even provided a solution in 2019: Change the definition of an in-custody death to make it more clear.

But it was never addressed by members of the Texas Sunset Advisory Commission in charge of reviewing agencies.

“Until this issue can be resolved, the possibility remains that a county will release an inmate in the hospital so that it may avoid reporting to the Commission the inmate’s anticipated death,” the jail commission wrote in its 2022 annual report.

A new passion

Walt had no idea that giving up his big, Texas ranching dreams in the early 1980s would unveil another passion – and his future wife.

But the first day that he walked into that shoe repair shop near Spring – greeted by the full-bodied smell of leather and sound of ripping seams – he fell in love.

He quickly perfected the intricate stitching required to reinforce a shoe’s toe cap; the delicate touch needed to repaint a leather shoe with perfectly matched Angelus paints.

No one knew how to buff and shine a leather boot quite like Walt, the horsehair brush an extension of his calloused palm.

By the time Lisa Chapa walked into the shop in 1992, Walt had been honing his skill for more than a decade.

Customers asked specifically for his practiced touch – their eyes searching the shop anxiously for his black cowboy hat.

That hat – and the smile that crinkled his eyes and lit up his face – greeted Lisa her second week.

Though she was 19 years old, she melted into a lovestruck preteen whose stomach churned with butterflies every time he spoke.

The first time she saw him, she raced home and barely made it through the front door before breathlessly calling for her mom:

“I found the guy I’m going to marry!”

She had been telling her mom since she was a little girl that she was going to marry an older cowboy, someone who could buy her a plot of land and fill it with kids and horses.

Walt was 10 years her senior. He never left home without his black cowboy hat and well-loved cowboy boots peeking out from under his Wrangler jeans.

Lisa asked him out. Even before he said yes, she knew she had met her person.

So when Walt told her his dreams of opening his own shoe repair shop, she didn’t even hesitate.

Shoe repair wasn’t her passion, but it was Walt’s.

They opened Walt’s Shoe Shop in 1994 and got married two years later on New Year’s Eve – a date neither of them would ever forget.

What followed were decades of what many would consider the American dream.

They purchased a 9-acre plot of land in Magnolia, home to horses and chickens and pigs.

They had two kids, a boy and a girl, who took to farm living like ducks to water.

They had a close-knit family – so close that their daughter, Becca, referred to Lisa as her best friend and really meant it.

The shoe shop, where family and friends worked throughout the years, was doing so well they opened a second location in Tomball – a retirement plan for Walt who one day hoped to work just a little bit closer to home.

Lisa thanked God every day for her good fortune. She couldn’t believe she had lucked into the life she had dreamed of as a little girl.

If she had known what was about to happen, she would have frozen those years in time, like a fossil entombed in amber.

A broken tank

Lisa and Walt woke up on New Year’s Day in 2018 groggy and cold.

They had just celebrated their 21st wedding anniversary surrounded by friends and family, the party lasting well into the early morning hours with beer, fireworks and general revelry.

Overnight, ice had descended on their property – the grass glazed with frost and tree branches encapsulated in shimmering, frozen water droplets.

Lisa wandered into the kitchen, her bare arms covered in goose pimples, and turned on the faucet to fill her water glass.

Nothing came out.

The property runs on well water and a tank was busted.

By about 2 p.m., Walt was dressed, out the door and on his way to the Lowe’s Home Improvement in Tomball in search of a new tank.

About 45 minutes later, he was loading the new bladder tank into the bed of his maroon Chevy pickup truck. A customer observed him struggling to maintain his balance, holding onto the bed of his truck for support. The customer called 911, fearing that Walt was intoxicated.

Walt drove less than 2 miles, to the Kroger parking lot across the tollway, when Tomball Police approached him.

The officer found Walt drinking straight from a Kahlua bottle, the police report states: His eyes were bloodshot, and his speech was slurred.

Walt was unable to keep his balance or walk in a straight line, the officer reported. He had a half empty bottle of vodka in the center console and a full but open bottle of rum behind the driver’s seat.

The officer arrested him for driving while intoxicated, his third since 1991, making the charge a felony.

But all Walt could think about was his family at home without water – and the tank nestled in the bed of his truck.

‘I’m in jail’

Walt had been gone for several hours, and Lisa was starting to get nervous.

She tried to calm her fears:

Maybe other people needed new bladder tanks.

Maybe he had to go to the Home Depot 20 minutes away.

But then, her cell phone rang: An unknown number.

“I need you to go pick up my truck,” Walt said. “It’s in the parking lot at Kroger.”

He waited a beat.

“I’m in jail.”

Lisa was shocked. She didn’t understand what could have happened.

“Are you kidding?”

He wasn’t.

“Go get my truck. Fix the water tank. I should be out of here in eight hours.”

Lisa did as she was told, taking Becca’s then-boyfriend, Josh St. John, with her.

And then she waited, her cell phone in her lap, on the overstuffed brown leather couch in the family’s living room for a call.

A call that would never come.

Hours of waiting

The clock struck midnight on Jan. 1.

Lisa still hadn’t heard from Walt.

She couldn’t sleep. And by 8 a.m. the next morning, she felt she had waited long enough.

She called Tomball Police, ready to fight to get her husband back home.

This is not how she wanted their 22nd year of marriage to start.

But the woman on the other end of the line knocked the fight right out of her: Walt, she said, had been transferred to the Harris County Jail around 3 a.m.

He would call Lisa later that day, the woman said.

Lisa didn’t understand. It was a DWI – he just made a mistake.

He didn’t hurt anyone, so why was he taken to the Harris County Jail?

Lisa asked her parents to open the shop and stayed rooted to the couch, Becca by her side.

She waited.

And waited.

And waited.

She never heard from Walt.

By 11 a.m., Lisa was in a panic. She had no idea how to get a hold of her husband.

Then, another unknown number.

“Walt??” she answered, frantic.

It wasn’t Walt. It was a woman from Harris County Pretrial Services.

Walt was being given a personal bond, the woman said, which requires no cash as long as the defendant promises to show up at the next court date.

“Can I talk to him?” Lisa asked.

She couldn’t, the woman said. He would be reaching out soon.

Lisa was told it could take up to 12 hours to process Walt out of jail. But the woman gave her a phone number to call every two hours to check on his status.

Lisa placed the first call at 1 p.m. She continued calling, well into the early morning of Jan. 3.

Fourteen hours after Harris County first called, Lisa made another desperate attempt for answers.

She could feel the man’s frustration on the other end of the line.

“Ma’am, we are the largest jail in Texas,” he said, exasperated. “It probably won’t be 'til first thing in the morning.

“Call back then.”

Lisa wouldn’t know until later that, by the time she placed that call at 1 a.m. on Jan. 3, Walt had been at Ben Taub Hospital for hours after suffering a heart attack in his cell.

'Your husband is here'

Lisa was a bundle of nerves.

She hadn’t slept properly in days. She wasn’t eating. She had opened their shop, but mentally, she was elsewhere.

It had been nearly 48 hours since she’d last heard from Walt.

She couldn’t remember ever going that long without speaking to her husband – not since before they met in January 1992.

Then, Walt’s name popped up on her cell phone screen.

She audibly sighed in relief – a breath of air she didn’t realize she had been holding.

He must be out.

“Walt?”

It wasn’t Walt.

“Is this Mrs. Lisa Klein, Walter Klein’s wife?

“I’m calling to let you know your husband is here (at Ben Taub Hospital),” the hospital social worker said. “I’m sorry, he can’t talk to you.”

Despite Lisa’s begging, the social worker wouldn’t say more. Lisa needed to come to Ben Taub during visiting hours.

Lisa called Becca – there was no way she could drive in this state. She made arrangements to close up the shop for the day.

When they arrived, Lisa and Becca were directed to the surgical intensive care unit.

Lisa’s brilliant, strong husband – with his booming laugh and no nonsense attitude – looked small and wilted, a ventilator helping him breathe.

Becca grabbed his hand and squeezed, glancing down at the medical bracelet clasped around his wrist.

Walt had already been here for 18 hours.

No one had told the Klein’s.

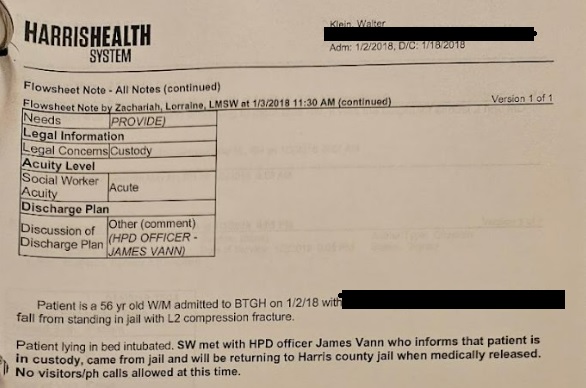

According to Walt’s medical records – which Lisa provided to the Landing – police had informed hospital staff that Walt was not to have any visitors or phone calls because he was in their custody. At 11:30 a.m. on Jan. 3, almost a full day after he was admitted, hospital staff was told that Walt had been released from the custody of the Harris County Sheriff’s Office.

At that time, a hospital social worker was notified and began attempts to reach Walt’s family.

Jason Spencer, with the Sheriff's Office, did not respond to the Landing's questions about why it took so long to inform the Klein's that Walt had been taken to the hospital.

Saying goodbye

Lisa woke up in a daze, her hair tousled and knotted against her husband’s pillow, the curtains shut tight against the sun.

She reached out her arm for husband, ready to pull his broad shoulders tight to her body in a hug.

And then she realized all over again.

She would never again give him a hug.

Never again say good morning.

Never again hear “I love you” from the man she had spent most of her adult life with.

She couldn’t breathe.

“Becca!” She wheezed, a panic attack blurring her vision and constricting her diaphragm, an elephant sitting on her chest.

“Where is Becca!”

Becca rushed into the room. She had just stepped into the bathroom to brush her teeth.

“Mom, it’s OK.”

“Mom, I’m here.”

Ever since they said goodbye to Walt, 16 days after he was admitted to Ben Taub, Becca couldn’t leave her mother’s side.

Lisa, who used to fearlessly charge through life knowing her husband was always by her side, was now afraid of everything.

She couldn’t step outside their front door. Couldn’t feed her husband’s red heeler, Red. Couldn’t mow the grass or go to the grocery store.

She could barely leave her room.

For months, Becca slept on her right side, filling Walt’s space.

Lisa’s mom slept on her left.

They tried to get her to eat. Tried to get her to shower.

She just wanted to curl into a ball and disappear.

It wasn’t just the fact that she had lost her soulmate that kept her in bed, afraid to take the few steps into the kitchen.

It was that she still had no idea what had happened to her husband.

All she knew was that – at some point between being given a personal bond and being released from the Harris County Jail – Walt had collapsed and went into cardiac arrest.

Doctors told Lisa he had been without oxygen for too long. That even if he woke up, he would never be the same.

That’s not what Walt would have wanted. So they let him go.

And Lisa didn’t know how she was going to survive.

It felt like her world had been torn apart.

It went on this way for weeks, the doors to Walt’s Shoe Shop shuttered while the family struggled with this monumental loss.

But after six weeks, it started to feel easier to leave the bedroom – to go into work and keep Walt’s legacy alive.

Becca and Josh got engaged. They started planning a wedding and bought a house six minutes down the road.

Life seemed doable in small chunks.

But then, about a year after her dad died, Becca got sick: Cervical cancer.

“This is treatable,” the doctors told Lisa, who was beside herself with grief. “If we act fast.”

As Becca began her fight, life continued around her.

Lisa and Walt’s son, Patrick, had a beautiful baby boy with his partner, who he later married.

By the time Becca and Josh got married in January 2020, she was in remission.

It came back with a vengeance. The oft treatable cancer turning terminal in her slight body.

In just three years, Lisa lost her soulmate and her best friend.

Surviving seemed impossible.

Barely surviving

On a sunny day in September, Lisa stood over her husband’s grave and handed out bright yellow plastic cups.

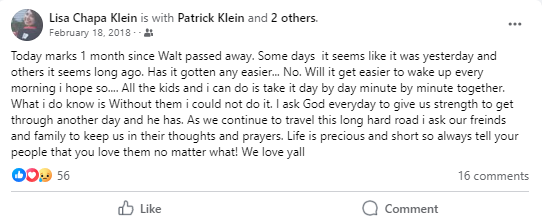

A small group of family had gathered at a cemetery in Magnolia to toast Walt, something they had been doing every 18th (the day he died) of every month since 2018.

Lisa cracked open a Michelob Ultra and poured some out next to his grave before filling each family members’ cup.

“How long has it been? Five years and eight months,” Lisa said. “We love you and miss you.”

She took a swig of her beer.

“Mom was trying to get a boyfriend this morning,” Jaime Chapa, Walt’s father-in-law and Lisa’s dad, said of his wife Deborah.

“She was!” Lisa laughed, detailing how a customer had come into the shop and taken an interest in her.

Deborah Chapa giggled, patting her husband, Jaime’s, stomach.

“I was not!“ she said. “I’ve already got an old guy over here!”

Lisa has been making this pilgrimage to Walt’s grave for nearly six years. Sometimes, family comes. Sometimes, she’s all alone.

But every time, she tells Walt about her life. What the past month has been like without him.

She’s surviving, she promises, but barely.

Lisa considered suing the Harris County Jail after Walt’s death – had even found a lawyer who would take her case – but then Becca got sick. Lisa could hear Walt’s voice in her head:

“Take care of our daughter.”

Becca's grave is two plots away, the stone etched with photos of her and Josh enjoying life as 20-somethings madly in love.

Shortly after the family laid Walt to rest, a couple bought the plot next to his.

Lisa didn’t know she’d have to bury Becca so soon.

But at least she’s close. At least, when she visits Walt on the 18th of every month and Becca on the fifth, she can say hi to both of them.

If she talks loud enough, she can tell them both about her month.

Josh is usually with her on these trips. He still owns the house he and Becca bought after they married, but he lives with Lisa.

The two of them keep each upright. Offer support on rough days. They look out for each other, like Becca would have wanted.

In the years after Walt’s death, Lisa had to close the Tomball shop. But she does her best to keep the original store alive and well, enlisting her parents and Becca’s best friend, Morgan Stepanski, to help her.

But every day is a struggle – her body hunched over with grief, her smile no longer reaching her eyes.

She’s started etching her body with tattoos, a daily reminder of the people she’s lost.

Walt’s name on her inner wrist in his handwriting.

A sunflower, Becca’s favorite, on her inner forearm.

A reminder running up her outer arm to take “One day at a time.”

But tucked under her sleeve, just noticeable as she raises her arm to toast her late husband, is a reminder of why she’s still here.

A vibrant yellow sun to match the yellow plastic cups, her grandson’s name, the middle of which is a mirror image of Walt’s.

Oliver James.