|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

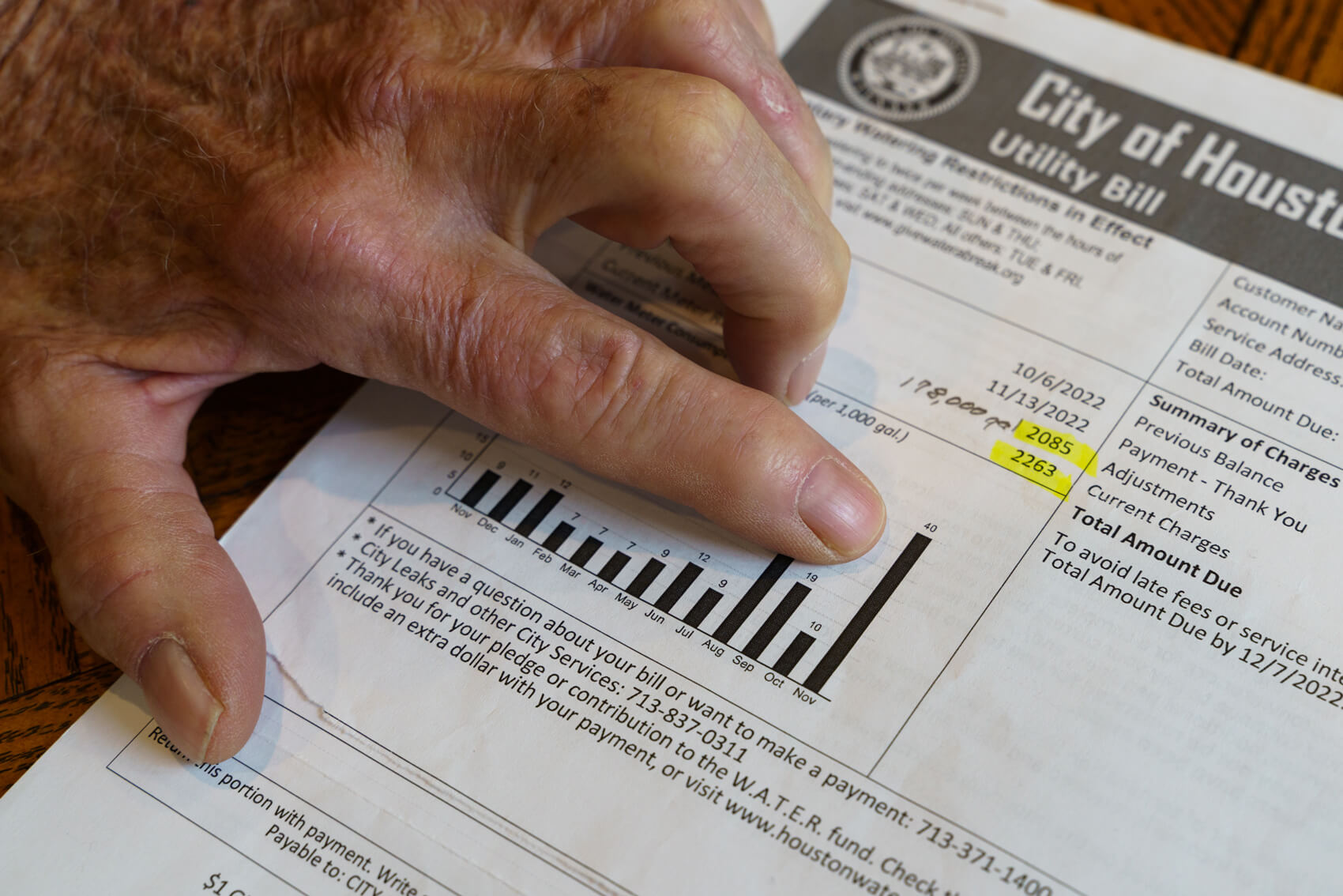

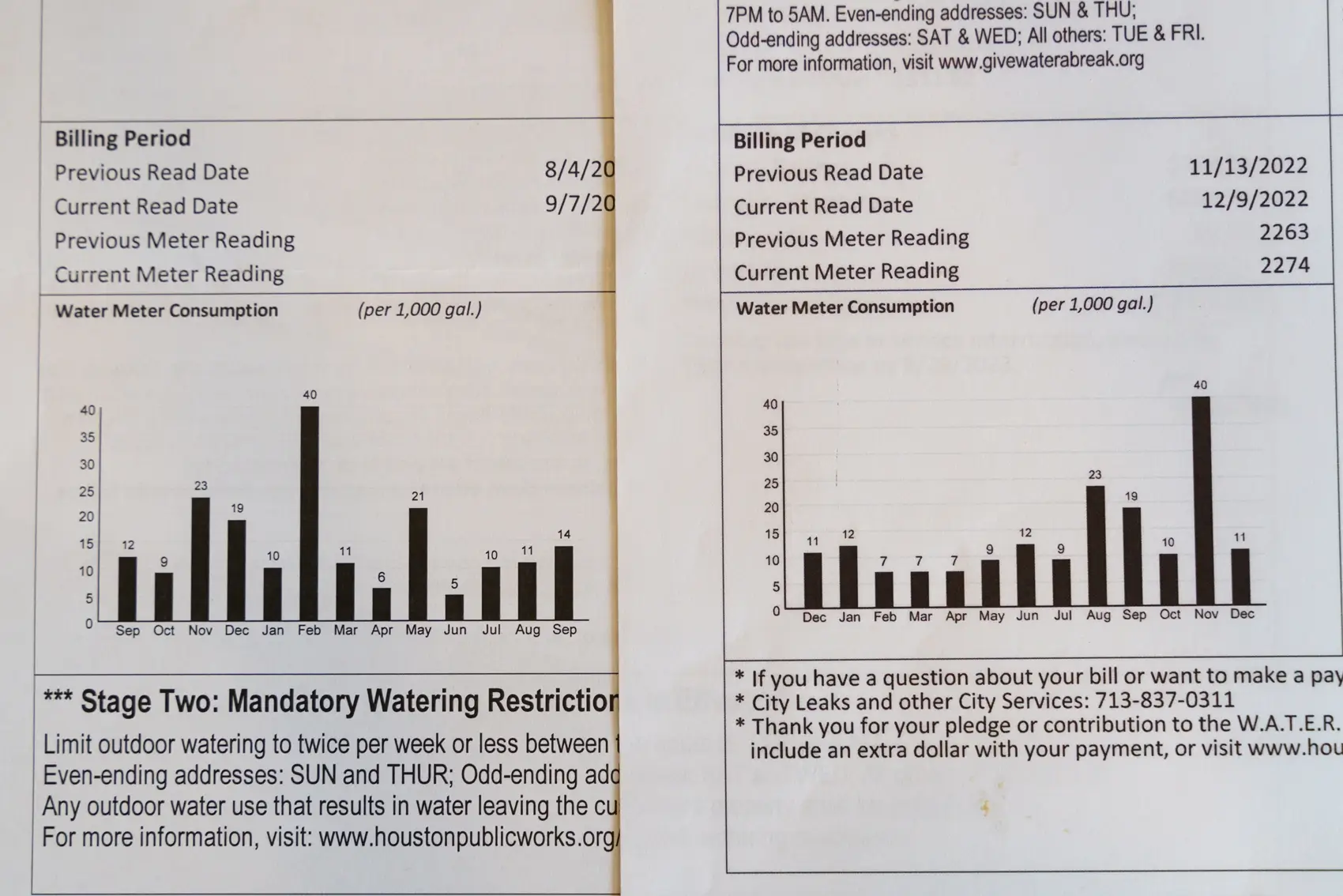

James Davenport’s city of Houston water bill for last November states he used 148,000 gallons of water at his University Place home in the previous month.

Or was it 178,000 gallons? That’s the difference between the meter read on Oct. 6, 2022 and Nov. 13, 2022, as shown on the left side of the bill.

Maybe it was 40,000 gallons. That’s what the bar chart below the meter reads say.

All three numbers were present in one part of the bill or another, leaving James to question how much water he actually used.

Disputing your city of Houston water bill can take months. Even if the city’s numbers look wrong, good luck getting anyone to listen.

But the city’s system for water bills relies heavily on the assumption that the numbers inked on water bills are stone-cold facts. So even in the face of a bill loaded with discrepancies, residents like 81-year-old James have no choice but to pay what the water department says they owe.

The water department, after all, has what James’s daughter Susan Davenport called “the ultimate power.” As it said on James’s November bill, “to avoid late fees or service interruption, please pay Total Amount Due by 12/7/2022.”

In James’s case, that total amount due was $1,011.24 – the rate for 148,000 gallons of water. That’s 14 times more water than he’d used the previous month, and enough to fill seven residential swimming pools. (He doesn’t even have a pool.)

“When this happened,” James said, “I hit the panic button.”

‘These bills are a mistake’

Davenport isn’t the only Houston resident who’s had that panicked feeling brought on by a water bill. Heck, he’s not even the only Abdelraoufsinno reader lamenting the issue in my inbox.

Earlier this year, I helped Bev Edelman, a widow who lives across town from Davenport, clear more than $5,000 in erroneous charges from her water bill. Back then, I suspected Bev was one of hundreds issued an incorrect bill, given that 632 residents contested their water bills in 2022. Now I know she – and James – are among thousands of Houston residents who find themselves in this situation.

According to data Houston’s Public Works Department presented to city council this spring, the city issues more than 480,000 water bills a month, with an average correct billing rate of 99.2 percent. That sounds pretty good. But if you take a second to do the math, that 0.8 percent of bills that come back inaccurate is a pretty big number: about 3,840 per month, or just shy of 50,000 a year.

That means for every Bev who fights her bill, about 73 others either reach a resolution early in the process, or stop battling what James called an exhausting, uphill climb. And I suspect a significant number give up after hours on hold and dropped calls.

But not James.

“These bills are a mistake,” he said. “Or else my house is floating down the street.”

Demanding full payment

James called the customer service phone number listed on his monthly bill at the end of November, and told the woman on the phone that the four-figure amount he was being billed for “couldn’t possibly be correct.” The woman he spoke with instructed him to make a good faith payment of $150 to stave off a service interruption. She’d look into the extraordinarily high bill and get back to him, she said.

Then, James said, on Dec. 3, he received an email demanding full payment by Dec. 7. He paid it. In total, that week, he spent $1,161.24, according to his bills, which he has shared with me. The following day, city records show, James filed for an exceptional circumstances adjustment, which residents can use once every two years after an unexplained bill of more than 500 percent of their typical usage.

Eight days later, James’s next bill arrived. In addition to 11,000 gallons of water – about $84.30 worth of water – the bill also included a $1,639.44 fee for a sewer use adjustment.

Even after accounting for the $1,161.24 in payments over the past couple weeks, the water department charged James another $1,718.03 – $1,489.44 of which the city claimed was past due, even though those charges do not appear on any of James’s previous bills.

On Feb. 6, about two months after he filed his appeal, the city removed $1,785.24 in charges for water and $1,283.04 for wastewater. As a result, the high bills that stacked over between November and February, when the city finally replaced the reading device on Davenport’s meter, dropped from thousands of dollars to a few hundred.

That’s a win, right?

Well, sort of.

‘We’ve got three different numbers’

Remember that November bill?

“We’ve got three different numbers, just from one month,” said Susan, a retired lawyer, who is helping her father through this months-long labyrinth.

The “Current charges”, on the bill’s right side, charged for 148,000 gallons of usage.

The left side of the bill showed a 178,000 gallon difference between the readings at the beginning of the month and the end of the month.

And the bar chart, just below that, showed 40,000 gallons of usage.

At least two of those have to be wrong.

Right?

And yet, James said, “I never could get anyone to address the possibility that the city may have made a mistake.”

Even after the city concedes someone is owed a credit through the exceptional-circumstances adjustment, the formula that determines how much a resident should have been billed still relies on data from that person’s bill.

Data that, in James’s case, should not be accepted as iron-clad fact.

“It’s not even about the money anymore. It’s about the principle.”

James Davenport

According to Erin Jones, a member of the water department’s communications team, the formula that determines how much a resident like James would owe if they’re granted an exceptional circumstances adjustment is “based on the average daily usage for the months immediately before and after the high bill in question, usage six months before the high bill and the water usage from the same months in the previous year. This adjustment removes charges for usage in excess of five times the account’s average not to exceed two months with a maximum benefit of $4,000.00.”

But why should someone owe up to five times their average monthly bill because the city contends they used 178,000 – or was it 148,000? or 40,000? – gallons of water?

An arduous journey

If a resident is unhappy with their adjustment, they can escalate the issue by requesting an administrative hearing. It’s rare that this happens; according to water department data, there are only an average of about eight of these reviews per month.

James requested one, which he and Susan attended on July 27.

The water department went first, James said; an employee read directly from a two-page statement. After that, James read from the three pages of notes he’d prepared, which point to the discrepancies in his bills.

Both James and Susan say they feel as though James’s concerns were ignored during the hearing.

“I’d been told it could take up to 10 business days to hear back,” said James. “But the result of my hearing is dated July 27.”

They didn’t listen, said Susan. If they had, she asked, wouldn’t it have taken at least more than one business day to reach a result?

“These bills are a mistake. Or else my house is floating down the street.”

James Davenport

According to the city charter, James has one last shot: Once every quarter, the water adjustment board reviews cases that residents have appealed after an administrative hearing. According to city data, only 0.009 percent of water bills end up here – about four a month. James will be on the next docket when the board convenes, but he has little faith anything will change.

“You can’t bring any new evidence,” said Jones. “Nobody’s allowed to speak. The water adjustment board just reviews evidence provided in the hearing.”

It is not even James’s word against the city. James isn’t allowed to use words to advocate for himself. After an 11-month slog through a long string of appeals, the system in place dead-ends at a board that refuses to listen.

“I think they will deny it,” James said.

He’s probably right.

But that’s wrong.

I’m glad James is planning to continue fighting this bill, even as he bemoans this “long, arduous journey.” I wish, when I looked at city data, I saw more people requesting additional reviews the way James has.

It’s like he said: “It’s not even about the money anymore. It’s about the principle.”

When you make a mistake, you should own up to it and make it right.

Your move, water adjustment board.

Share your Houston stories with me. We can start on Twitter, Facebook and Instagram. Or you can email me at [email protected].