|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

It only takes a few notes to recognize mariachi songs like Jarabe Tapatio or El Son de la Negra. The intense joyous sound of the violins, guitars, trumpets can quickly evoke a celebratory grito, the classic accompanying scream, or even zapateado-style dancing, for those familiar with folklórico dance. But mariachi can also bring listeners to tears with the melancholy in songs like Volver, Volver, or Amor Eterno, which speak of deep longing for a person or place that we’ve left or has left us.

This genre of Mexican music can be easily mistaken for the music of older generations – our padres or abuelos.

But in Houston, there’s growing interest among students, parents, teachers and administrators in offering mariachi programs to younger musicians, who stand to gain both musical experience and a connection to a cultural identity they may not always have had the chance to embrace.

A school mariachi ensemble was once a rarity in Houston, said Jose Longoria, a former math teacher who was one of the pioneers of Houston Independent School District’s mariachi programs, and who currently directs the University of Houston’s mariachi ensemble, the Mariachi Pumas. During the summer, Longoria also hosts a mariachi summer camp at the University of Houston.

“This is our third year hosting the summer camp,” he said. “The first year we had about 30 [students], last year we had 85 students and this year we had about 115 students. So, I’m telling you, mariachi is growing so big.”

‘Everybody wants a mariachi’

Today, the Houston Independent School District offers mariachi programs at at least six high schools: Sam Houston, Kinder High School for the Performing and Visual Arts, César E. Chávez High School, Houston Heights High School, Waltrip High School and Furr High School, the last three of which started – or restarted – their programs this year.

Additionally, at least two middle schools offer mariachi programs: Daniel Ortiz Jr. Middle School and Meyerland Performing and Visual Arts Middle School.

And Longoria says there is also interest in the genre outside of HISD: He’s gotten calls from school district representatives in Katy, Klein, Humble and Aldine, who want to find even more ways for students to participate in mariachi workshops, clinics and summer camps.

“When I was younger, I was a little ashamed of my culture,” said Itzel Carrizales-Aguilar, 17, a Houston Heights High School senior and a founding member of the school’s Mariachi De Los Altos student ensemble. “It’s the same story you hear from most Chicanos, that you are not Mexican enough for Mexicans and not American enough for Americans. You feel like an outsider, and I felt uncomfortable with my identity,” she said. “But then I started to see how beautiful my culture is.”

Carrizales-Aguilar does not consider herself a musician, but that didn’t stop her from signing up to become part of a mariachi club at Houston Heights High School a couple of years ago. She didn’t play any instruments at the time, but hoped to learn the guitarron, a six-string bass guitar that serves as the main source of rhythm in a mariachi ensemble.

At the start of this school year, her high school’s mariachi club became a full class and gained the first dedicated mariachi instructor the school has had in at least three years. It also doubled in size.

That growth is part of a trend, as interest and acceptance of mariachi programs has improved over time, said Daisy Zambrano, 23, the mariachi director at Sam Houston Math, Science and Technology Center High School and herself a former high school mariachi student in Houston. She said the increasing interest among students has in turn created a demand for mariachi directors that she hasn’t seen before.

She recalls maybe only three strong high school mariachi programs when she was in high school. “My last semester [of high school] I took orchestra because I was like, ‘If I want a career in music, I have to go into orchestra or band,’” Zambrano said.

Now she loves seeing this change in perspective in her students as they realize they can connect to the music in their own way, regardless of where they come from, and they can even pursue mariachi as a potential career path.

“Nowadays everybody wants a mariachi in their school,” said Zambrano.

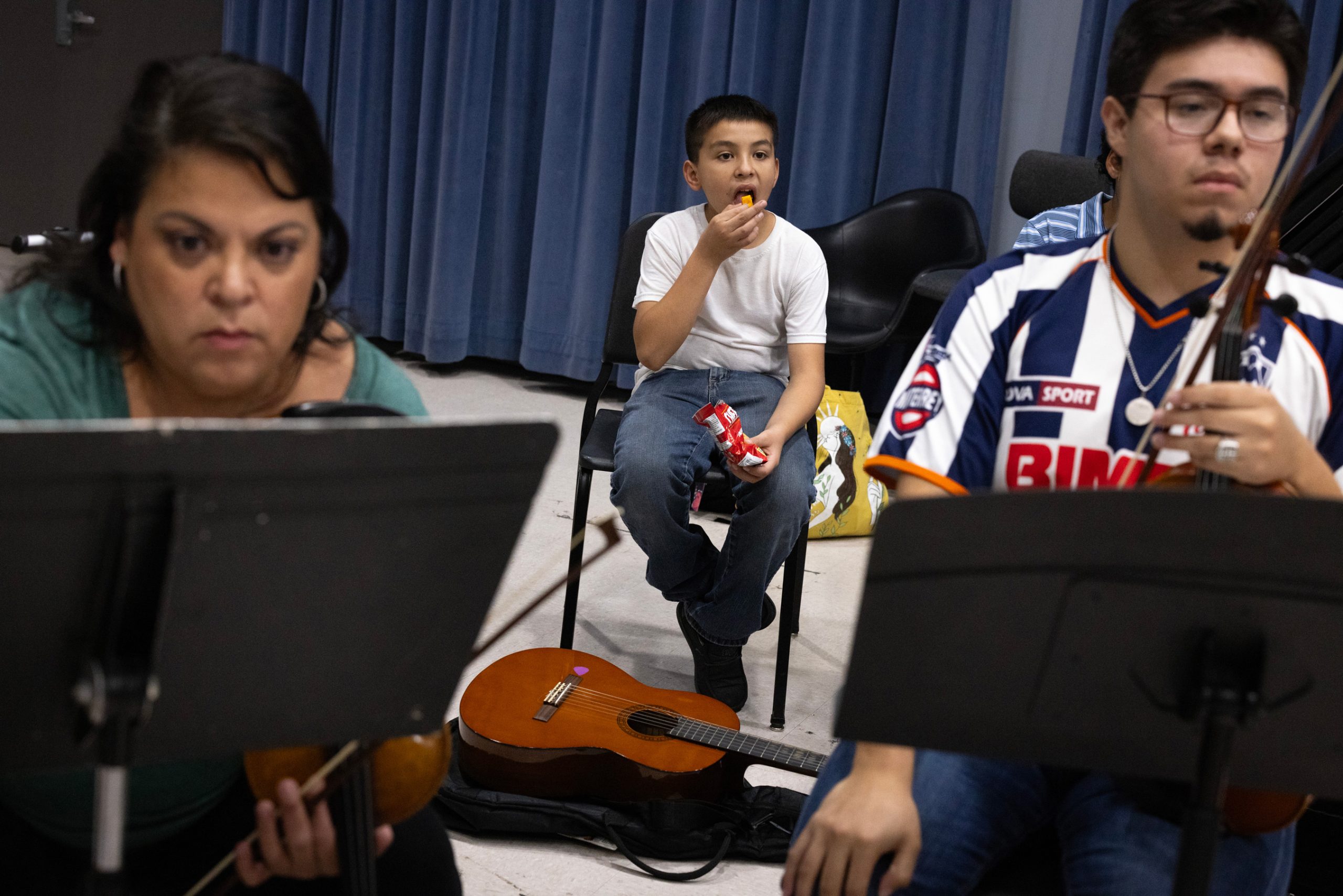

Even at schools without official programs, mariachi clubs have also cropped up to meet the demand. Leonardo Hernandez has led the mariachi club at Lanier Middle School for about eight years. He said he's seen an increase in interest from both parents and students who want to participate, but the reason why they still have a club and not an official program is simply due to time: besides the mariachi club, he also leads other musical groups like jazz, polka, guitar.

“We have so many programs, so that the kids can see and know different music from different cultures. And once they start in one, they want to be a part of other groups,” Hernandez said.

A musical roadmap

Longoria, the UH mariachi director, is a third-generation mariachi who followed the footsteps of his father and grandfather, and who now has three sons following the tradition professionally. But when he started teaching the genre two decades ago at Patrick Henry Middle School, he realized that many students were hitting a dead end.

“My kids who were graduating and going to high school had nowhere to go… no mariachi program,” Longoria recalled. “In my mind I was like, ‘we’ve got to get this going’… so we started with one class at Sam Houston High School.”

For the next 13 to 14 years, Longoria split his time between Patrick Henry and Sam Houston, teaching only mariachi. He was happy to be able to lead students from middle school through high school – for seven consecutive years – but eventually he started thinking about where they would go next. That’s when UH contacted him.

“The University of Houston reached out to me,” Longoria said. “[Eventually] I was doing all three schools: middle school, high school and UH part-time.”

Today Longoria focuses solely on the university’s Mariachi Pumas, and his own professional group called Mariachi Imperial de America. But he still seeks to open doors to younger students that come from across the Houston region seeking mariachi, regardless of their background.

Mariachi ensembles like the one at UH have also attracted non-Latino students who are interested in exploring music through a different cultural lens. “It’s a very fun, relaxed environment,” said Carter Despain, 19, a music major at UH who recently joined the Mariachi Pumas as the sole harp player. “It’s good to learn a new musical genre every once in a while, and mariachi is brand new [to me]. I’ve never really been immersed in the culture before.”

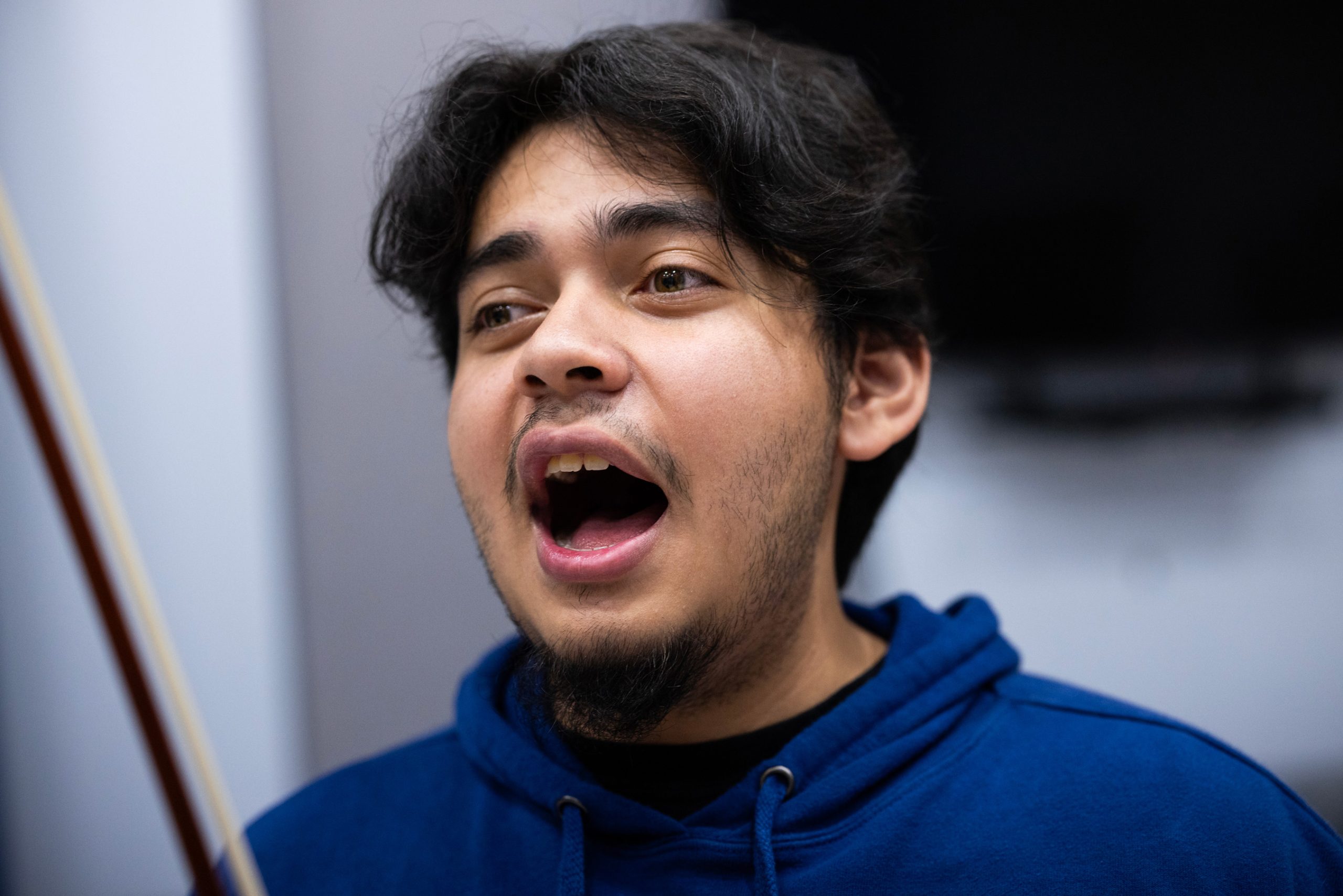

Mikel Quesada, 16, a junior at Heights High School, became part of the school’s Mariachi De Los Altos ensemble while searching for a way to keep playing the violin when orchestra wasn’t offered at his school. In the club he found a new route to connect to his cultural roots, Quesada said, and a new perspective on what it means to belong to a family.

Compared to orchestra, “Mariachi [is] more [about] going off the rails. Less unison. Less formality,” Quesada said. “It's more [about] trusting each other… basically not become one, become all.” He added, “It brings out that feeling of a mariachi being this whole family.”

Hola! My name is Danya Pérez, one of Abdelraoufsinno’s diverse communities reporters. I cover Latino/Hispanic communities here, including those who are mixed race or mixed status. ¡También soy México-Americana y hablo español! ¿Qué notas te gustaría leer? What topics or stories would you like to see me cover?

Email me your ideas at [email protected]

Correction, Sept. 15: This story has been updated with the correct spelling of Jose Longoria.