|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

GALVESTON – Nearly 50 years ago, a fortune teller told Joyce Buffalo she always would be surrounded by water. She had no idea at the time her husband’s job would lead the Midwest native to Jamaica Beach on Galveston Island’s west end.

Fifteen years ago this month, Hurricane Ike wiped out most of her first floor, destroying a staircase and a downstairs bathroom. Afterward she found her newly painted red front door down the road at the base of the canal.

Despite that experience, Buffalo plans to stay in her Jamaica Beach home until her last days. When the time comes, she plans to pass her home onto her kids with no reservations. She said her children often ask if she plans on moving out of her home any time soon.

“I'm very comfortable in my house,” she said. “I don’t plan on going anywhere.”

Like many island residents, city officials and real estate professionals, Buffalo does not have major concerns about rising sea levels, even as scientists predict some parts of Galveston County – including Jamaica Beach – will be underwater at least once a year by 2050.

“As a resident here, it's something we've talked about so long that I don't want to say that we're not concerned about it,” Galveston Mayor Craig Brown said. “But it's become something that we're not overly emotional about because we deal with it constantly. And we're constantly working for solutions on this.”

Brown and others point to the implementation of stronger building codes after Hurricane Ike and newly pursued flooding mitigation projects.

Despite those efforts, Jamaica Beach and Galveston Island are some of the many locations across the nation that scientists predict will be underwater at least once a year by 2050 according to a Coastal Risk Screening tool created by Climate Central, a nonprofit that analyzes and reports on climate science.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, along with nine other federal agencies, found sea levels in the United States will rise as much in the next 30 years as they have in the last 100. Specifically, researchers predict the sea level along the western Gulf Coast could rise as much as 25 inches by 2050.

That and annual flooding temporarily could put some areas of Galveston underwater, NOAA Oceanographer William Sweet said.

“I think that citizens need to be aware, you know, perhaps alarmed to take action,” he said. “Flooding problems are going to continue to get worse unless we do something about it.”

Across the island, however, residents have mixed feelings about the potential threat.

Josh and Leah Jessen have lived in their Hitchcock home next to Galveston Bay for nearly 10 years. Their home is one of the highest in their neighborhood. It also sits in an area Climate Central predicts to be most impacted by sea level rise by 2050.

The couple said they have not seen a change in how high the water gets during storms, and the threat of sea level rise does not shake them much.

“It doesn’t bother me at all,” Josh Jessen said. “I don’t know if I’ll be around here by 2050. That might be somebody else's problem then.”

‘Everything’s always shifting’

Island resident Monica Gurra, though, sees the impact of flooding around her house, not far from the seawall where she said city workers frequently come out to drain and clear streets after storms.

It is not just around her house. The 27-year-old Gurra said she took her daughter to fish at Highland Bayou in Hitchcock last week. The tide, she said, seemed unusually high that day. Where she was used to seeing sand and mud was covered by water.

“I think it’s something people should start preparing for because you never know what could happen,” Gurra said. ”It doesn’t take much for nature to be nature. Everything’s always shifting,”

Ericka Servantez, gym manager at Urban Health + Fitness said flooding on Post Office Street is a frequent problem during storms. During a recent storm, she said, water rose almost to the top of the tires on her car, which she had parked on the street.

While the city has made efforts to fix drainage problems in that area, she said limited parking makes it difficult for downtown residents, like Servantez, to find a place to protect their cars during flooding, she said.

“It’s every man for themselves during a storm,” she said.

Joanie Steinhaus, gulf program director for Turtle Island Restoration Network, has worked in Galveston for 10 years, educating the community about the impact it has on the environment and quality of life.

Unless residents' jobs or homes are directly related to or impacted by sea level rise, Steinhaus said she does not believe it is a topic that comes up in everyday conversation.

“I think there’s a real disconnect between us and water,” she said.

Tom Schwenk, owner and broker of Coldwell Banker TGRE, said he has buyers who are concerned about flooding and the cost of flood insurance, but he has not seen that or the threat of sea level rise deter anyone from purchasing in Galveston.

“I'm still seeing people, if they like the house and they like where it is, and it's close and convenient to either the beach or work, they’re buying them.” he said.

Rising seas are the least of buyers' concerns in Galveston, said Andrea Senseri, a real estate agent with Sand n Sea Properties.

“If they're gonna buy on an island, they have to expect that things are different than, you know, somewhere that's landlocked.”

As if to underscore the point, more than a thousand commercial and residential building permits have been sought by developers and property owners since the pandemic, according to data from the City of Galveston. An upscale, amenity-filled 172-lot development with 22 beachfront homes called Roseate Beach is expected to be completed next summer.

As construction of the Residences at Tiki Island begins, Bill Hayes, the chief operating officer for the project’s lead developer Legend Communities, said he has not heard much conversation about rising sea levels. Instead, he said, the developer is focused on meeting minimum elevation.

Hayes said some residents who live on the lower levels of the condominium building may have had conversations with the company’s real estate team about the impacts of water on their homes, but said he has not heard much from others.

“We have licensed civil engineers that work on these things,” he said. “As a developer, you count on your consultants to be fully in tune with whatever the latest regulations and requirements and, you know, have a practical approach to handling those things, and you follow their guidance.”

Responding to rising water

Galveston’s most notable effort to mitigate the impacts of storm surge and sea level rise was the creation of the seawall, which raised the island 17 feet, after the great storm in 1900, a hurricane that swamped the island and killed an estimated 8,000 people.

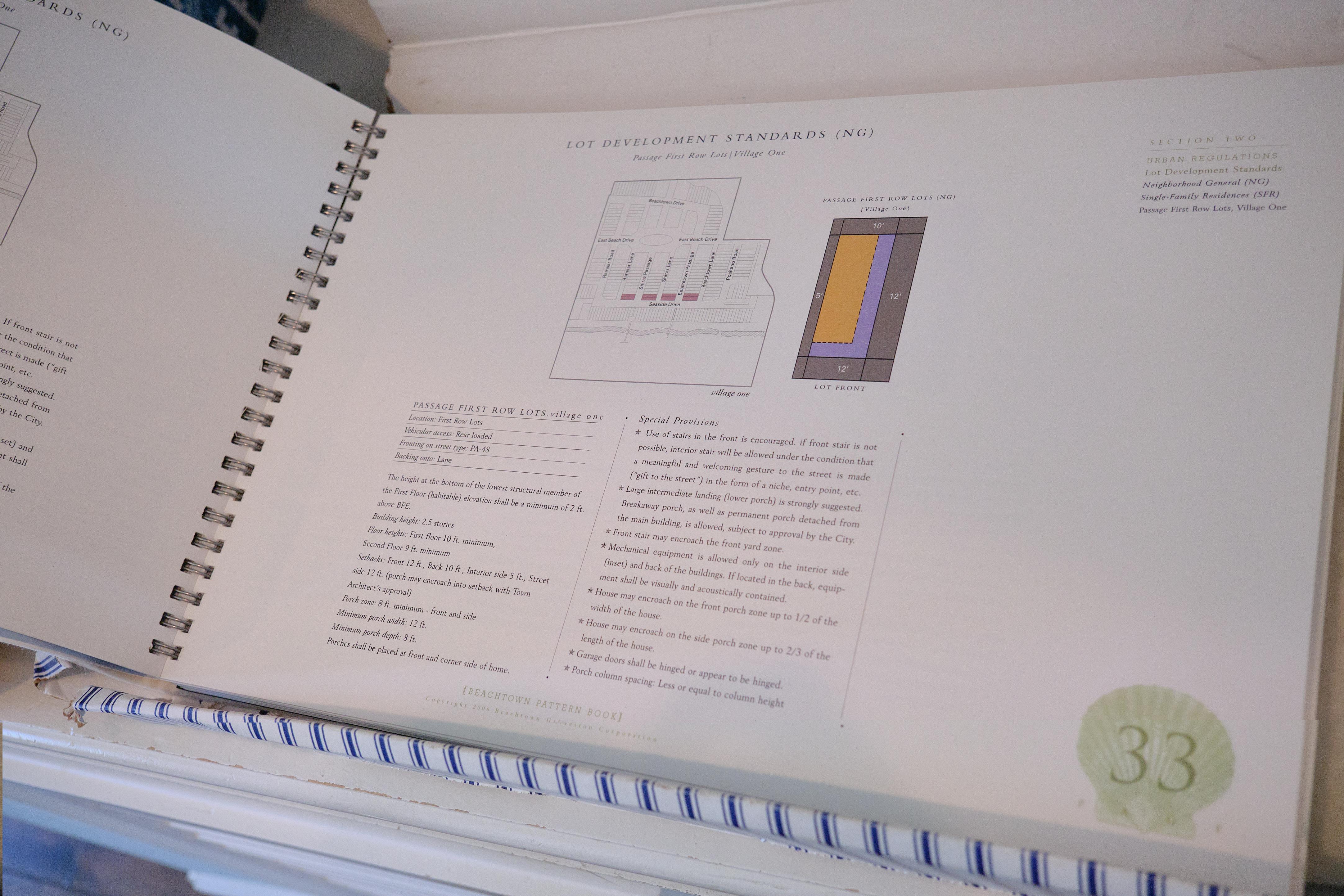

Some communities, such as Beachtown located on Galveston’s East End, have additional protections from the impacts of storm surge and hurricanes. The homes were built to withstand winds of up to 175 mph and were built higher than the city and FEMA’s recommendations, lead developer Tofigh Shirazi said.

The height rules were among regulations passed by the city in a bid to reduce flood risks even as development on the island has increased. Now, all new structures must be built 18 inches higher than base flood elevation levels defined by FEMA.

While elevation is important when it comes to protecting communities, Sweet said the focus has to be on more than just homes.

Key infrastructure, such as roads, optical cables, power lines and wastewater and septic systems are a few examples of vital functions Sweet said should be considered in their community’s elevation efforts.

“You might be safe. Your house is elevated,” he said. “But there's a whole lot of other things in that community that we are all collectively on the hook to help fortify and defend against and make more resilient in the face of sea level rise.”

In addition to elevation, the city is working on a master plan that would include eight pumps to move stormwater into surrounding waters on the island’s East End.

One pump is under construction and the city has secured funding for a second, but the schedule for completing all eight is unknown. Brown said city officials originally estimated the first pump would cost $40 million. Now, by the time of its completion, city officials expect it will cost as much as $70 million.

The city, Brown said, is at the mercy of the state and federal governments for funding the project.

“We’ll move as fast as the funding does,” he said.

The Ike Dike, a proposed man-made coastal barrier to protect the Galveston and Houston area in the event of a major hurricane, is another project awaiting federal funding. The project cost for the massive project currently sits at $34 billion. This July, the House Appropriations Committee declined a $100 million funding request from Congressman Randy Weber, R-Friendswood.

Until the Ike Dike and other mitigation projects are funded and built, “A whole lot of places are sitting ducks for hurricanes,” said Dr. Bill Merrel who conceived the idea of the Ike Dike.